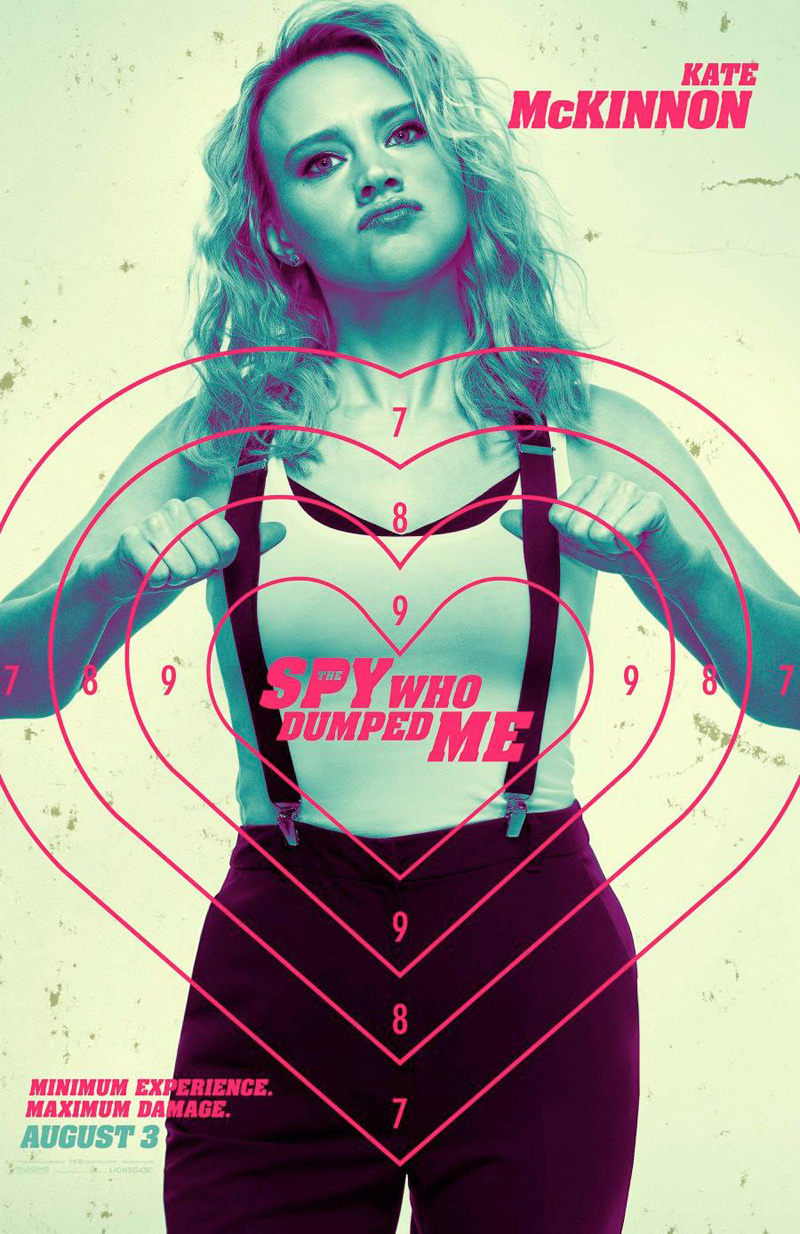

If there’s any crime The Spy Who Dumped Me has committed, it’s being too damn smart for its own good—but in the best way possible. That doesn’t necessarily come by way of ass-kicking, nunchucks-swinging female action sequences, though it is technically a spy movie. It is how it refreshingly presents its two heroines—Audrey and Morgan (Mila Kunis and Kate McKinnon)—as wonderfully human, beautifully complex, and ridiculously entertaining, who find themselves at the center of a dangerous spy mission after the former’s boyfriend suddenly dumps her.

Store clerk Audrey and her best friend and wannabe actress Morgan aren’t characters you typically find leading car chases, manipulating international assassins, or narrowly escaping death, but, as the film underscores, women always find a way to rise to the occasion when the situation demands it. What this duo may lack in Atomic Blonde-like abilities, they make up for it in cunning, fake-it-‘til-you-make-it tactics that even surprises them. Even more profound is how their ironclad friendship is woven into an increasingly high-stakes narrative and serves as the fuel that keeps the two grounded when everything seems so impossible for them.

That’s also what compelled director and co-writer Susanna Fogel to tell this story—the opportunity to present an actual thriving, positive female friendship rooted at the center of a spy comedy, something we rarely ever see in the genre. Here, the filmmaker talks to us about obliterating action movie tropes, writing flawed female characters that matter, and how she responds to the political weight of being a woman director in the age of Wonder Woman.

ComingSoon: The Spy Who Dumped Me is so fun! It was everything I never knew I always wanted. It really surprised me.

Susanna Fogel: That is the highest honor. What surprised you about it?

CS: One of the things I really surprised me is that it’s not your typical badass female action hero, where the central character already has impeccable fight skills and knows how to use these crazy weapons. These two women don’t know how to do any of this, but somehow figure it out and stumble their way into finding their own greatness. They also have these moments where—in the midst of utter chaos—commend themselves by saying something like, “You’re freaking awesome. I don’t know how, but we’re doing this.” I really appreciated that.

SF: One important thing was to show a friendship. I have fatigue around watching women bicker and tear each other down, which isn’t to say that those conflicts aren’t also realistic sometimes. I hadn’t seen as much of this encouragement and love and support that categorizes so many of my real-life friendships. I wanted to put that in the genre. In traditional action movies, people’s feelings aren’t validated. They’re not really the concern of the movie. But I felt like it was such a specific thing to show for women. It personalizes the genre where action stars are kind of robotic ass kickers. That’s progressive, but it could also set a different trope in motion that we would have to then balance with other examples.

CS: Like you said, we don’t see friendships in actions movies with a female lead. Usually she’s by herself and equipped with amazing skills. She seems very cold and not one to have friendships.

SF: They’re so problematic most of the time. When there are best friends, one is usually the star and the other is this sidekick, just the comic relief and way too preoccupied with wanting to talk about their friend’s love life all the time. There are so many ways friendship is shown that is not the true, “You’re my person. We’re going to take on the world.” In the case of this movie, that means an insane plot. I like bringing real emotions into the equation.

CS: A lot of that is embedded in Kate McKinnon’s character who stops in the middle of some high stakes drama to tell her friend how incredible it is that they’re even pulling this off. Then she calls her parents (hilariously played by Jane Curtin and Paul Reiser) to update them, and they’re equally supportive.

SF: My and cowriter David [Iserson]’s background as writers is grounded in indie movies or TV dramedy, cable dramedy worlds. So, what we find funny as we move throughout our day is this observational funny, Larry David-type stuff; the inner neurotic workings of our Jewish family back east, and how many hours early do our parents need to get to the airport, and all this relatable stuff. Even down to our families coordinating for the premiere. They’re basically the characters you see in the movie. It’s like, “How do I find you?” “What if I need a snack?” To us, that is the funniest stuff. The observational stuff of true comedy, like being a person. If we were putting ourselves in the situation of Mila and Kate’s characters, we would still have those parents. We would still need to pee. We would still be lactose intolerant or whatever. We always felt like that was the best way to do something different in the genre, introduce those moments that you never see in the traditional action movie.

CS: It does really ground those characters. I even insert myself into movies like this and I think, “Oh, that’s how I would react too” or “I don’t know what I would do in this circumstance.” As crazy as the plot gets, it still seemed rooted in something so relatable and genuine.

SF: We would always put ourselves in their shoes, and then ask, “What would happen?” “What would you do?” and of course we would all laugh because we’d be like, “Well, we’d be dead in five seconds.” In the crazy world that is this movie, what’s real? We have these moments where you think about stuff and one thing that changed a lot in terms of a reality check is that the script has a lot more hard jokes on the page that were funnier in a joke way. When we were shooting some of these sequences, the girls were like, “This is not a moment where I would make this joke about French food” or whatever. “I wouldn’t be doing that.” It was really collaborative. If you were to transcribe the script we got, there would be fewer jokes in it, but it feels a bit deeper now because it doesn’t take you out of a moment to pause for a joke.

CS: I felt that. I know you wanted to make this a movie that contradicted tropes we’ve seen in the past, but were there any particular movies of or related to this genre that inspired you in any way during the filmmaking process of this movie?

SF: When Dave and I were first paring out what the movie was, we referred to it as Broad City meets Bourne in our conversations over lunch. Like, “What do you want to write? Let’s try to mash up these genres.” In reality I think the friendship story to us is so in the DNA of what we write. It’s so instinctive, I can’t even think of other movies that do that. It’s so in our nature to write about that. In terms of the genre, we were kind of giving a mini tribute to different styles of genre that we really liked. So, each action sequence there is sort of “in the vein of.” We wanted the opening to be in the vein of Bourne in terms of how the camera worked, the colors, the editing. Later there are more stylized sequences. We were thinking, “What is the tone of this sequence and what type of movie is it? Is it the grounded, everyman side of Bourne? Is it like hyper stylish like Bond?” The car chase was like us doing our version of that. It was pulling from different inspirations from different types of the movies.

CS: I read the interview you did with The Hollywood Reporter recently, where you talked about the “political weight” of being as a female director and having to respond to a specific issue or have a certain responsibility. Was that something that was on your mind while making The Spy Who Dumped Me? And what do you think it would take to no longer have that pressure, where successful female directors are the status quo?

SF: I think it’s just going to be a matter of having more representation. The first time someone does something, it’s talked about and dissected and think pieces are written about it: “Who is Wonder Woman?” “What is this movie that a woman made about a superhero?” “Let’s talk about it as if it will never exist again.” It’s a great movie and it should make room for more. It’s a challenge because I take that pressure seriously and I want to represent women in a positive way. But I also don’t want to present these women in a flawless way because showing them having flaws is considered anti-feminist by some blogger who’s going to crucify me for saying this. Sometimes they can’t drive stick (a direct reference to a scene in The Spy Who Dumped Me). I happen to be able to, and my male writing partner can’t. That scene is about Americans in Europe. It’s not about women being bad drivers. But everything gets politicized and everyone is sensitive and really reactive right now. Which is a good thing, and I’m feeling that responsibility. But it can feel scary to think about. It loads every choice you make if you let it. If you’re coming from a place of respecting your characters, that’s all you can do and there will be people who will not like that for whatever reason. But not caring about that is very hard—especially for women, because we are raised to care about what everyone thinks.

The Spy Who Dumped Me is in theaters August 3.

The Spy Who Dumped Me

-

The Spy Who Dumped Me

-

The Spy Who Dumped Me

-

The Spy Who Dumped Me

-

The Spy Who Dumped Me

-

The Spy Who Dumped Me

-

The Spy Who Dumped Me

-

The Spy Who Dumped Me

-

The Spy Who Dumped Me

-

The Spy Who Dumped Me

-

The Spy Who Dumped Me