Welcome to a special edition of CS Score, soundtrack lovers! This week we’re jumping right to the chase to get to our amazing interviews with Jeff Russo, composer of hit shows such as Fargo, Star Trek: Picard, Lucifer, For All Mankind and Clarice, among many others. We also got a chance to speak with composer Osei Essed, who has worked on the documentaries Accept the Call, True Justice: Bryan Stevenson’s Fight for Equality and the recently release Amend: Fight for America.

Let’s get to it!

NEWS

We’re excited to announce seven amazing soundtrack LPs for @recordstoreday‘s 2021 drops: The Matrix 3-LP set, Village of the Damned deluxe-edition double LP, The Iron Giant and The Goonies picture discs, and Shrek, Ghosts of Mars, and Aliens limited-edition color LPs. pic.twitter.com/mOoL3apSKA

— Varèse Sarabande Records (@VareseSarabande) April 7, 2021

Here are your two clues for the CD Club titles coming this Friday. Who will be brave enough to take a bold step with their guesses and compete for the chance of getting the highly coveted “good job” reply from the Varèse admin? pic.twitter.com/jB0wkqCOOb

— Varèse Sarabande Records (@VareseSarabande) April 28, 2021

Available to order now at https://t.co/M4LZNDtqCp – The #TimeTunnel Vol One: 3-CD Limited Edition #Soundtrack Set by Johnny Williams, Lyn Murray, Paul Sawtell & Robert Drasnin ! #IrwinAllen #TV #60s #JohnWilliams pic.twitter.com/yipJQgSQj1

— La-La Land Records (@LaLaLandRecords) March 16, 2021

GateWorld and @LaLaLandRecords are giving away the new STARGATE 25th anniversary soundtrack. PLUS: Join us for a special live conversation with composer @DavidGArnold!https://t.co/DftRuplJFx

— GateWorld.net (@GateWorld) April 29, 2021

Congratulations to Trent Reznor, Atticus Ross, and Jon Batiste on winning the Academy Award for Best Score for #PixarSoul! #Oscars pic.twitter.com/9gw6LyM2sq

— Pixar (@Pixar) April 26, 2021

JEFF RUSSO INTERVIEW

Emmy-winning and Grammy-nominated composer, Jeff Russo is creating some of the most varied and compelling music for television, film and video games. Russo earned an Emmy Award, and two additional nominations, for his score on FX’s Emmy Award-winning and Golden Globe-winning series Fargo. His music can be heard on CBS’s Star Trek: Picard; Star Trek: Discovery; and Clarice; Netflix’s Cursed; Altered Carbon; The Umbrella Academy; Apple TV+’s For All Mankind and Starz’s Power. Past credits include Hulu’s The Act, FX’s Legion, Starz’s Counterpart, Noah Hawley’s feature film Lucy in the Sky, Mark Wahlberg’s action-thriller film Mile 22, Craig Macneill’s Lizzie and more. Russo also received a BAFTA nomination for Best Music for Annapurna Interactive’s video game, What Remains of Edith Finch.

Jeff Ames: You are the renowned composer of shows like Fargo, Star Trek: Picard, Lucifer, For All Mankind … how did you get to where you are today?

Jeff Russo: [Laughs] Oh, boy. What a long road! Well, it’s hard to answer that question because so much of any success at anything is being in the right place at the right time and being prepared for an opportunity; and an amount of luck. What I mean by luck is, you know, happenstance — I know, so many people who are really great at what they do and haven’t had as much success as I think that they should! There’s so much of that involved. There’s so much in the right place at the right time with the right music and the right personalities in the right room, and the right project for everything to sort of come together. And then for that to actually become something successful, that leads to something else successful, it’s such a domino effect. The circumstances of anybody’s life lead up to the moment that you have when you sort of stepped into a new chapter. Nothing I ever did as a teenager, nothing I ever did, as even a young adult, would prepare me directly for what I’m doing now. And I never expected to do what I do now.

So, speaking on that, how did you get involved with TV and film composing?

So first, there’s a moment where you become interested in something. And I sort of credit that to, I was asked to act in a movie and play the guitar player/roommate of some other person who lived upstairs. And I did that, and the composer of the movie and the director asked me, knowing that I was a guitar player — which is how I got hired for the job — to come into the composer studio and play guitar on the score. Now, that composer’s name is Ben Dector, and he became one of my best and dearest friends. And as I did that, I thought, “This is kind of fun and kind of cool.” Like, you know, maybe one day I’ll play again on a score — that would be fun. My band then went back and toured and made more records, and five years later, I ended up talking with a very good friend of mine — her name is Wendy Melvoin of the duo, Wendy and Lisa. And they suggested that I come to the studio and watch them do what they do. They were working on a number of shows at the time. I hung out with them in their studio, watched what they did, and then eventually, they asked me if I would want it to work at all with them as an assistant — and I did! I got coffee and did all kinds of stuff, set up studio, set up sessions and edited stuff. And then finally, they asked me if I wanted to write a cue or two for something, and I did, and that’s where I sort of got a start at writing music for television.

After that, it was three years before I actually got a job on my own. It was literally being in the right place at the right time and knowing the right person who could then introduce me to the right person. I have a very good friend — he’s an actor, his name is Jeremy Renner — and I ran into him accidentally — I haven’t seen him in like a year and a half. I ran into him at a restaurant, and I said, “What are you doing?” And he’s like, “Oh, you know, shooting a pilot right now.” And I happened to ask, “Do you guys know anything about whether or not they have a composer?” And he did. He called me the next day and said, “Hey, we talked to the producer. Go ahead and send in a demo.” So, I did. They liked the demo. And then I had a meeting with the showrunner, and they hired me. And that person was Noah Hawley. The show [The Unusuals] only lasted for one season, but then we did another show. And then that same showrunner did Fargo, and then that turned into many other things.

So, I guess my point here is that there isn’t a real answer to that question. I wish there was. It would be very easy if there was. So many things go into what happens in the long-term part of someone’s career. I’ve been doing this for 12 years, and it’s hard for me to draw a line from where I am now, back to that moment I walked into that restaurant.

And, as you mentioned, while there is luck, you still had to have the talent to land the job.

Yes, of course. So, the point I was making is, it’s not just about having the opportunity. It’s about being ready for the opportunity when it presents itself. Right? And so all of those things need to line up — you have to have the right music, you have to have the right thing altogether. You know?

Now, you’re the composer on all of these cool projects. Was there a moment where you stopped and realized that you made it?

I mean, every time I look around, and I’m writing on some cool project, I pinch myself. So, Star Trek and The Umbrella Academy, and, you know, one thing leads to another thing leads to another thing … Every time I sit down in front of my workstation and I start to write something, and I look up at the screen — it’s never feeling like, “Oh, my God, I’ve made it here!” It’s always like, “Wow, I can’t believe I’m sitting here working on this great thing!” It’s unbelievable to me that I continue to be able to do this for a living and to make music, and to work on great projects. So, there’s never a moment where I’m like, “Wow, I’m here!” I think the moment you think that, I think you’re done.

What is the scoring process that you go through to find a show’s musical identity?

It’s different for everything. There isn’t a single process. You know, I read a script. I sort of sit around and try to envision what that script sounds like. I try to envision what a particular character feels like, and what I would like to convey, and how I want to support the storytelling.

Finding the right sounds or finding the right melody, that’s, I think, something I just don’t know how to describe. It just happens. I just find something, I find a little melody or find a cool sound or a cool instrument, or I try to create something new or try to build a new instrument or try to make a sound on an instrument that I’ve never done before; and see if that inspires an idea. For music, you know, it’s really about finding the inspiration to write something. It’s not just about sitting around and writing something. You have to have the inspiration to write something. Sometimes it’s about finding what that inspiration is. And I can spend a week, a month, three months trying to find something. On something like Fargo, I have a good amount of time because I usually get scripts very early in the process. So, I have time to sit down and think about something and then put it away for a minute, then come back to it, and then put it away for a minute, and then come back to it with the hopes that at some point, I’ll sit down and go, “Oh, yeah, this is cool. Let me show this to Noah and see what he thinks.” That’s happened on pretty much all the projects that we’ve worked on. And I try to do that with every project. Not every project allows that. So, in that case, sometimes you literally sit back on things that you know, sounds that you know, and ideas that you’ve already had. I don’t mean musical ideas. I mean process ideas.

RELATED: Noah Hawley Teaming With Ridley Scott for Alien Series at FX!

For a series like Fargo, how do you keep the music fresh for not only the audience but yourself as well?

Each season is definitely its own musical challenge. I’ve had to basically abandon all themes, except for the main title theme, for every season. And the idea was, it’s a new story, it’s new characters. The only time I’m able to utilize themes from other seasons is when the characters actually crossover. And except for the one theme, the bad guy theme, which is this drumbeat that I did in season one called “Wrench and Numbers” for those two characters in season one and season two, I used it as a means to convey the bad guy strut, basically. In season three, I used it because one of those two characters appears in that season. So, I was able to bring it back in that way. And in season four, I used it in a very subtle, subverted way because I just wanted to have fun with it.

The Emmys are right around the corner. You’ve won before, but what’s it like to win?

Winning is an incredible feeling. To know that your peers really think that this is work that is worthwhile of their accolades. You know, it’s a really wonderful feeling to have your peers say, “Yeah, this is good work. And we think this is among the best work of the year.” I feel like there’s so much good music on television nowadays. It really has risen to a level of real art. It’s really, really great. And, you know, all of the people who are involved in the television Academy — having those people stand in judgment of your work and to all agree that this is worthy of being in the top of the field … maybe not the top top, but just to think it’s risen to this level is a really, really incredible feeling.

How do you feel you have evolved as an artist over the years?

You know, it’s funny. I feel like the longer you do something, the more confident you get. But what I’ve realized is everything is new every time. And that’s something that I really cherish is the ability to make art and use that to help further a story and have it be something that I can do on an ongoing basis. So, I think that, as I’ve done this for a while, I’ve become more confident in myself, and yet I’m always trying to regain that feeling of new. So, every time you do something, it’s like a weight. You know? Yes, I’m confident in the way I feel about this, but is it gonna work? What’s the director gonna think? What’s the producer gonna think? What’s the studio going to say? You know, it becomes less about what they’re going to think and more about whether or not it’s going to work.

You know, you definitely start out a career fending off rejection, which happens at all levels — rejection happens at all levels. The top composers have been fired. The top composers have been passed over for jobs so that that never stops. But what I think happens, as you get more and more into doing it again and again, you become a little more self-confident in your own work — about how you feel about it — so that rejection, or that note, doesn’t actually make you feel bad about yourself. It makes you understand that it’s not about you, it’s about the work, and that it’s not necessarily a direct reflection of a person. But you get a little more confident in, “Well, I made this decision because I made this decision. It’s okay for you to not think that it’s the right decision, and I’ll fix it to make it more of what would you want it to be,” because I do this in service of someone else’s art, right? So, you just become more accustomed to that and more okay with that. And that a level of confidence that you can only gain by doing it again and again and again. And I think that’s what I gained a lot of in the last 12 years. It’s not about I’m right, and you’re wrong, and what I think is the right thing and what you think isn’t the right decision. It’s just more about being able to be collaborative in that way and understand that it isn’t directly related to my person. So, I don’t take anything personally.

OSEI ESSED INTERVIEW

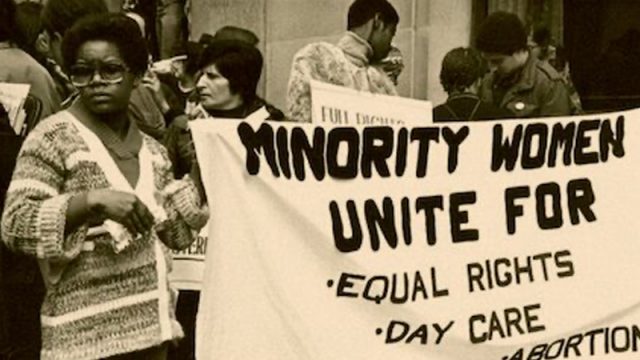

Osei Essed is the composer behind the new Netflix documentary series Amend: The Fight for America, executive produced and hosted by Will Smith and featuring a number of luminaries including Mahershala Ali, Diane Lane, Samuel L. Jackson, Pedro Pascal, and Yara Shahidi, among others. The six-part series explores the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution—which, in 1868, promised liberty and equal protection for all persons—as America’s most enduring hallmark of democracy.

Amend has wall-to-wall music, including Osei’s score, which is intermixed with inspiring pop hits throughout. Osei knew the music had to be able to travel across time—starting from when the 14th Amendment was ratified 153 years ago. Given that this amendment is central to the everyday lives of Americans, he felt it was especially important for him to find the right tone musically.

Osei describes the score as “modern minimalist, meets orchestral Americana.” The composer is a lover of simplistic music and making textures interact with harmony and various instruments. English horn, bass clarinet, and electric guitar are some of the most prevalent featured in the music. [Adrianna Perez]

Jeff Ames: What drew you initially drew you to this particular project?

Osei Essed: Well, you know, there’s always a bunch of things working at once. So, the idea being that I could tell a long-form story — it was sort of my first run diving into that form of storytelling. And then, of course, the subject matter itself was really intriguing. The idea of this single amendment affecting so many different parts of our everyday lives and so many different kinds of people that I know — all of our lives, daily.

Ames: How does your approach to this style of storytelling differ from other, more traditional styles? And was there a particular episode that you started with that helped inform your score?

Essed: Well, firstly, you want kind of a unified color and set of themes — that solution throughout the series — so finding those elements, it turns out, is somewhat similar to scoring a documentary. But because of television, there’s a lot of fast cuts. So at the same time, it’s long-form, because it’s more than one episode, or it’s more than one two hour set of stories, it’s also really kind of these little tiny worlds that you have to craft fully before moving on to next and sort of make them feel as if they can move seamlessly through 45 minutes or an hour. And then, across a six-part series, those moments have to speak to one another, have corollary moments so that it feels like you’re watching a cohesive piece of piece of work. Obviously, directors and animators and producers … everyone has their part, and I play mine.

I did start with one episode. I started with the “Love Episode,” episode five. And that one really turned out in many ways to be the most personal story of the series. So, and because of that, it allowed for more intimate, emotional cues to be written. And then, it was easier to cross apply those ideas in small form throughout the rest of the series. Not necessarily, you know, wholesale, but certainly finding inspiration from those moments in the love episodes.

Ames: How much freedom do you have when producing a score? Are you given a certain amount of direction from the producers and directors? Or is it a blank slate? Bring us some music, and then we’ll work from there?

Essed: It really is a combination of both of those things. I mean, there was music temped in, so there was a guide there for pacing and such, but there was a lot of freedom and trust from the producing team and the producing partners and from the directors; and everyone in terms of music. We talked about things, and that kind of communication made it so that there could be trust.

RELATED: Netflix Cancels The Duchess After Just One Season

Ames: Were you able to integrate new music or instruments that you hadn’t used before?

Essed: I got to use woodwinds a little bit more than I have in the past and in these interesting new ways. That was really exciting to me. And it’s sort of combining woodwinds at times with electric guitars or with synth set — those sounds together are a sonic universe that I haven’t yet explored. So, it was exciting for me to really — I mean, I got to use voices in combination with one another that I hadn’t been able to use before. And I got to use a more expressive form of musical storytelling because that’s what was required in this circumstance. I think there were so many dynamic moments and so many opportunities to really stand out a little bit frequently in documentary. Even when we’re pushing, which I have been fortunate enough to get to do quite a bit in a documentary, but, you know, to do it across six episodes gives you a little bit more leeway.

Ames: What was the initial reaction to your musical cues when you first wrote them?

Essed: It was generally positive throughout, all around. And, you know, most of the time, when there was anything that needed to be redone — you know, the edit went a lot of different ways. The series is pretty forward-looking in terms of documentary format. So, there were a lot of different approaches that were tried. And then when we settled on something, on a voice obviously, I had to amend cues for that. But also, you know, sometimes the pacing wouldn’t be exactly what we were looking for. And so, you have to sort of find the way forward together. And we really, really did, and it was pretty gentle all around, you know? There wasn’t a whole lot of push. There was very open and honest [discussion], like, “Hey, this one isn’t working,” and, “Can you go and do it again?” I never take for granted that my first one or two tries are going to be the thing. It’s nice when it is, obviously. We’re all hoping to sharpen our ears with each new project. But I don’t ever expect that everything’s gonna be right on the first try.

Ames: Where does your inspiration hit you? I’ve read interviews where composers say they discover a theme walking through the supermarket. Is that the case with you?

Essed: You know, I just generally have some sounds happening in my head most of the time. And as soon as I start realizing those sounds on any given instrument, or in any form, usually, they change. And I try to respond to that. And sometimes the sound, whatever it is that I’m hearing at any moment, I can just say, “Okay, well here, this is what’s going to happen.” And then, as soon as I explore that, I discover, “Well, maybe it’s actually not that. Maybe it’s something that responds to that that was actually happening in my head, and I just haven’t heard it yet.” So, I don’t really have a clear response. I come from songwriting, and I remember when I would write songs every day, there would be maybe a lyric in my head or a small melody. I don’t really work where there’s a sudden realization. I think it comes, and it grows, and it changes and I try to react to it and stay open.

Ames: What drew you to the world of film scoring?

Essed: The first films that I was asked to work on were documentaries. I’m really excited to tell stories with music. The music that I wrote as a songwriter, I always saw as functional music. So, I would always try to use folk music from different parts of the world; and then just blending into the way that society functioned. And just being a part of everyday life and storytelling, in film, at this point is really a part of our everyday life. We watch television, we watch movies, and it’s an integral way of storytelling and the way that we see ourselves and understand each other and understand one another. So being able to tell stories alongside filmmakers is really exciting.

Ames: How would you say your process has evolved over the years?

Essed: When I first started, I only wrote for instruments that I could play, or nearly play; and occasionally instruments that I knew folks who could play because I played with them in bands or in a group. So, it really started with the familiar and has sort of grown from my comfort zone to like, well, how far from what I know can I go? Before, I had to ask questions.

Ames: Do you have any other projects that you’re working on?

Essed: Oh, boy, well, I just finished a wonderful documentary — Dear Mr. Brody. I’m really excited about and am always excited to be working with Keith Maitland. So that was a great project to work on. I just finished a really deeply moving film called And So I Stayed, which is yet to find a home. We’re just wrapping up; we’re going into the sound mix. And that one is a very exciting film. I got to write for synth and strings for that project, which is a lot of fun. The story itself is not fun. It’s a story about women incarcerated for killing their abusive partners and sentencing guidelines. And it’s told in a very in a very different form. So, it’s not talking heads. It’s not just information, but it’s walking through lives of people affected by these stories. I can’t say enough about how effective it was to see these stories every day for a few months.

Ames: A lot of the films that you tackle are very heavy-handed. How much of your personal life experience do you bring into these projects? And does the work have an emotional impact on you in any way?

Essed: I try to be empathetic, and I’ve used the word a few times. I try to be open and allow people’s experiences to move me. There are historical narratives sometimes, and sometimes there are present-day narratives, and I just try to make sure that I’m open to how people might experience them. And I try to carry that into an oral world.