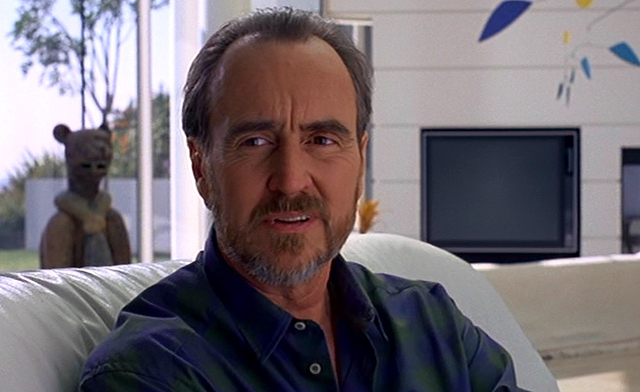

Shout! Studios provided ComingSoon.net with the chance to have an exclusive chat with Bob Shaye, former head of New Line Cinema, on his new horror thriller Ambition, which opens in theaters in NYC, Los Angeles and select U.S. cities tomorrow, as well as Digital and On Demand. Check out the interview below!

In the gripping, suspenseful thriller, Jude is an intense, driven musician preparing for the biggest performance of her life – but her ambition could end up killing her. As her competitors begin to die bizarre deaths, she recognizes a pattern that seems to connect her. Is she next? Her suspicions are confirmed in a shocking climax that puts into question her chances for survival, and her sanity.

From the producer of Nightmare on Elm Street, Ambition stars Katherine Hughes (Kingdom, My Dead Ex), Giles Matthey (Submerged, Once Upon a Time), Sonoya Mizuno (Devs, Crazy Rich Asians, Maniac), and Bryan Batt (Mad Men, Billionaire Boys Club) with a special appearance by Lin Shaye (Insidious series, The Final Wish, Room for Rent).

Directed by Bob Shaye, the film was produced by Bob Shaye, Michael Lynne, Sarah Victor and Unique Features.

ComingSoon.net: It’s been over 10 years since you were behind the camera. What drew you to the script for “Ambition”?

Bob Shaye: Actually, what drew me to it was not so much the story per se, but the fact that it had—and I’m not sure the writers even completely understood this, it had for me reminiscence of the scene from the very first short film I made, “Image”, a long time ago. It’s a little bit about how do you know what’s real? And one of the things that came to my mind when I started reflecting on the script, and I went back and forth on it for six months. Really the story needed a lot of work and there was a whole bunch of issues, but the one thing that really, really compelled me was this idea that—and it’s now come so much to the fore, it’s like a version of fake news. How do you know what you’re seeing is real? And it reminded me of a commercial I saw for Dyson vacuum cleaners a long time ago on television.

CS: With Fred Astaire?

Shaye: Yeah, exactly. It’s funny, it’s great that you know that. I even spoke about that at a conference once. I said, I don’t know what’s true anymore. I saw Fred Astaire dancing with a vacuum cleaner. And people looked at me like I was crazy, but now you see what’s going on and there’s this whole thing about even with Epstein and whether the guy’s hands were his hands or some other fat guy’s hands or somebody around a girl. I mean, you don’t know what to trust. You’re seeing, believing is really the issue.

CS: I remember years ago hearing some effects guy talk about how he could’ve taken the Rodney King tape and make it look like Rodney King attacked the cops. And it just terrified me.

Shaye: No, it’s true. It’s part of what a horror film is. Who’s in your bedroom at night? You see a shadow, is there somebody there or is that just my imagination? So this first film I made, “Image”, was just about that. I mean, it’s actually a whole line of philosophy. I don’t want to get into that, but how do we know what’s real and how do we know, period? And now, it’s quantum mechanics and all that other stuff, where the same thing can be in two different places at the same time. I mean, what’s that all about? People can’t trust their own logic and their own sensibilities. So in this case, I sort of liked this idea, even though it’s a kind of a poor imitation. But I think this film made, in a kind of Douglas Sirkian style, which is meant to be very formal and not too flashy. And actually, that’s why the DP, who really developed the format, was really drawn to the story, too, because he liked it. So there was a kind of a hint that there’s something awfully formal going on here and it’s not really the eye of the director, it’s something else. On this case, obviously, it’s the eye of the character. The film plays out and I thought that I could end up with a film that appealed to millennial females, particularly, who I think are a great niche audience. New Line had its whole successful part of its career built on dealing with niche films that major companies didn’t care about, up to and including horror films and John Waters and people like that and “Reefer Madness”. We always looked for the stuff that was for niches. And I thought that millennial women were very liberated these days, and really might appreciate a film that is a bit of a thriller that also is entertaining and is all about them as opposed to somebody else made it a perfect niche opportunity. And so, that’s what got me involved.

CS: One of the things that actually struck me the most about the film was that when I watch so many horror films these days, the palette is generally very desaturated, very drab, and this movie was the opposite of that. You had these big, bold colors. It kind of reminded me, you mentioned Sirk. I thought of Powell and Pressburger, “Red Shoes”, something like that.

Shaye: Well, that’s all good. The point is that it’s all being seen through this girl’s eyes, and that’s how she saw life, strange boys playing guitars and doing all that stuff and then turning out to be bad people. That was what she saw and that’s what we saw.

CS: And but did you discuss with the cinematographer about using that specific palette and saturating the colors?

Shaye: Yes, it was supposed to be cheery until it got not cheery anymore, but it doesn’t happen until the rainstorm comes. It’s supposed to be kind of a halcyon world for this girl, except that she has this incredible ambition and she’s not going to let anybody tell her that she can’t achieve it. And even her friends are telling her to lighten up and she says, “Remember, the opposite of tension is slack,” and the girls look at her crazy, but she has an ambition. She’s a young woman who’s going to be a concert violinist and is going to win, and nothing was going to stop her.

CS: Sonoya Mizuno was so good in “Ex Machina” and I just saw Giles Matthey in this great little horror movie called “1BR”. And then you have Katherine Hughes. Can you just talk a little bit about your cast?

Shaye: Well, the cast, I was very pleased with them. They showed up from a casting director and we did interview a number of actors who were all quite good. It was a bit of a challenge for some of the people to get them to be interested in the film because a suit was directing, so to speak. We had our regular epiphanies and disappointments, but I thought we put together a terrific cast. I thought everybody did an excellent job and they really got into the movie and there was a lot of ad libbing that worked out. And they sort of got it. So I was quite happy with them.

CS: There was some trepidation of having someone in your place of power behind the camera. Do you do anything to diffuse that tension on the set?

Shaye: Well, I mean, I try to be a good guy and I try not to get into arguments with the actors. And the way I try to approach it is to really co-opt them, at least when they’re not doing what I want them to, just tell them, do it your way and then give me a couple of takes to do it my way and we’ll get it together and have the editor look at it to decide which one works, just to get it out to film. But I don’t think I’ve had any confrontations. I was just telling somebody about—when we made “Alone in the Dark” and we had Jack Palance and Martin Landau as two of the actors. And Jack Palance gets his first night call and he won’t come out of the trailer. And so, I said to the executive producer, “What’s the trouble?” He said, “Well, Jack wants to talk to you.” So I go and say, “Hey, Jack. We’re going to do a rehearsal now.” He said, “I didn’t tell you, I don’t want to work at night.” So I said, “Jack, the name of the movie is ‘Alone in the Dark’. What did you have in mind? A closet?” I said, “It is in the dark.” So he went back into his trailer and I sent the executive director in to talk to him again. He came back and he said, “It’s true. He did read the script and he did realize it was in the dark and that he had to deal with it. But the other thing he did is he doesn’t want to kill anybody.” I said, “It’s about three homicidal maniacs who break out of a mental institution and terrorize the family. Somebody’s going to be killed. Who’s going to do it?” He said, “Well, I’m not doing it. I don’t believe in violence.” Jack Palance. I said, “Okay.” So we had to take a couple of murders away of what was happening and give them to other characters like Martin Landau and this other guy Erland van Lidth and because Jack would not have anything to do with any murder. So it’s a challenge, and that’s kind of one of the fun things about being a director, is really kind of co-opting actors into a point of view or not getting into an argument with them. And also, knowing when enough’s enough, you know, when you do 23 takes of a car pulling away. It gets everybody on edge and it doesn’t help the production. So it was done, and particularly because it was on a lower budget, too, with a modicum of preciousness. And I thought we got the performances that I wanted and it came out fine, in my opinion.

CS: I am so happy that you brought up “Alone in the Dark” because it’s one of the most unsung horror films out there. You worked with Jack Sholder several times, and obviously, you wrote the story for it. Does it hold a special place in your heart, even though it’s not one of the better-known New Line films?

Shaye: Sure, it does. It was not my first film, but it was the first one that I actually physically was really the producer on. And it was all-night shooting, and it was really exhausting. And Jack and I still have kind of a complicated relationship. But hey, he ended up cutting some of the trailers for the first films we distributed, the two Czech films that we distributed to colleges. Of course, I’d known him for a very long time. And yes, of course, it has a special place for me. In fact, the guy who was the executive producer, Benni Korzen, who’s a dear old friend of mine, too, has just brought us the possibilities of doing a remake for “Babette’s Feast” because he’s a Danish producer. I’m still close with a lot of those people there for sure.

CS: In particular, I’m obsessed with the ending of that film for some reason, where Jack is in the punk club and he sees that woman.

Shaye: It’s funny you remember that, yeah. And he sings that song, “Chop Up Your Mother”. That’s Jack Sholder’s taking things a little bit too far, but that was funny. And that was an interesting thing because with that film, where he holds up the gun and then the film ends, I said, can’t we have a gunshot or something? There’s got to be some kind of finality to it, a finish, something that the audience—and I know, and filmmakers continue to do that, they have those open-ended endings, which aren’t really endings at all. It’s like having a book that doesn’t have an ending. You wonder, did I really spend my time wisely sitting here for an hour and a half or two hours and seeing a film that doesn’t have a satisfactory resolution, which really takes in fact “Elm Street”, too, and the discussions that Wes and I had about the ending of that film. But it’s possible if you’re an auteur and that’s how you want to do it, but it’s a little bit disdainful of the audience, because they’re looking for the appetizer, the main course, and the dessert. And if you cheat them out of the dessert, they might not come back to the restaurant, if you’re using the cooking analogy.

CS: Yeah, I guess I’m a weirdo, but I liked the ambiguity of it and I liked the weirdness of it. I just love her last line where she’s like, “Hey, Face, you’re really there.” But you brought up Wes Craven, obviously you had a long relationship with Wes and “New Nightmare” was kind of a precursor to what he ended up doing with “Scream”. He was just such an interesting filmmaker because if you were lucky in your career, you do one movie that sort of defines the zeitgeist or defines the genre. In the 70’s, he did “The Last House on the Left”, 80’s he did “Nightmare” and 90’s he did “Scream”. And all three of those movies sort of define the genre for those decades.

Shaye: Yeah, but you notice because he was a little bitter about “Nightmare on Elm Street”, they were so successful, that he didn’t want to do the sequels. He didn’t want to have anything to do with any of them. And we definitely offered, I begged him to do it, and he just said, “I’m done. I’m moving on.” But “Scream”, of course, was making fun of “Nightmare on Elm Street” the whole time. In fact, there’s even lines, I think, where somebody, I think it’s Drew Barrymore says something like, “It’s not that ‘Nightmare on Elm Street’ movie. It’s somebody really scary.” I forget what she ways, but it’s a really intentional barb that caught me right in the throat, frankly, but it was okay. We ended up being very good friends, and I regret his passing tremendously. He was a really talented guy. He made that violin movie with Meryl Streep. It was really interesting. He tried to get away from all this stuff.

CS: People forget he was this very soft-spoken college professor. He wasn’t a maniac or anything.

Shaye: Exactly. But “New Nightmare” was a big surprise. He called me five or six years afterwards and said, “How would you like to really do this?” And of course I thought it was fun because the truth of the matter is, deep in my heart I wanted to be an actor, but when I got started in the progression, I realized that I was a terrible actor and I also realized that the first good lesson in life is to know what you could do well and what you can’t do well. And don’t pursue the stuff to make a living that you can’t do well. And so, I stopped being an actor. But I think it shows in my performance, so it’s a little cringeful, what the hell.

CS: You played yourself very well. Something that’s avant garde, 20 years later it becomes wallpaper. The idea of doing a meta horror movie at that time was kind of far out. But nowadays, it’s a total normal aspect of any kind of pop culture. As a studio head, your tastes tended to lean more towards… in not the avant garde, then definitely towards the more left-of-center type of concepts. You’re very business savvy too, so how do you reconcile the artistic leanings versus what’s going to make a buck?

Shaye: The truth is, my artistic feelings, I keep pretty much to myself and I try to infuse them into the entertainment. I try to sneak them in where I can. And I also try to stay true to the theme of the movie, the genre, respect the writing and the actors. And it’s such a collaborative process for me. I’m not much a believer in the auteur theory of moviemaking altogether that there’s not a lot of stuff that I absolutely insist on. There are some things as the backbone of the movie that you just can’t change because somebody doesn’t like the lines or something. So there is a place where I just say, “Please do it my way and let’s move on.” But we’ll do it your way once and we’ll see if that works just to kind of placate them. But just because it’s written on the page doesn’t mean that that’s how the film’s going to come out. And there’s lots of surprises in the production process, lots of great ideas and sometimes things that just don’t work at all that are confounding to the max, where you just don’t know what you’re going to do, and everybody’s just down. One that happened with “Town and Country” with Warren Beatty.

CS: That was a crazy production because that kept getting re-shot.

Shaye: No, he closed the movie down because he didn’t like the script. And so I said, “Well, why did you take the movie, if you didn’t like it?” He said, “Well, I thought I could fix it.” I said, “Well, listen, you’re the actor. Give it a break.” That was one thing. Another thing was with Marlon Brando. I don’t know if you happened to see the Netflix documentary about “Dr. Moreau”.

CS: Oh yes. It’s amazing.

Shaye: John Frankenheimer called me out of the clear blue sky. I knew he was directing the movie eventually, after we fired that guy. And then he calls me up and he says, “You don’t know me, Bob, but I’m in the middle of nowhere in Australia and I just had the most incredible thing happen. I had to call you to tell you about it.” And I said, “What’s that?” He said, “I’m driving Marlon to the set to do rehearsals. And he asked me to stop the car. I stopped the car and I said, ‘What’s wrong?’ And he said, ‘I got an idea. Let’s tell Bob Shaye.’ And he said, “I’ve never had an actor say that about a producer, but he said tell Bob Shaye.” He said, “I don’t like the script. I think what we should do is just close down the production. Let’s you and I work on the script and let’s do it the way I like it and you like it. And let’s just throw the regular script away.” I said, “I don’t think we can do that. It’s what I was hired to do, is direct this movie.” He said, “No, it’s all wrong.” He says, “And I have the perfect ending for it and I think this is what we should do.” So John’s telling me this story, he said, “Well, what’s the perfect ending?” He said, “I’m going to be wearing a hat during the whole movie as Dr. Moreau and at the end I’m going to take the hat off and I’m a dolphin.” And Frankenheimer says, “Did you know this, Bob?” And I said, “No, he’s a dolphin?” I couldn’t believe it. He said, “Yes, he said he wanted to be a dolphin, so I thought I had to call you and tell you this. Things did not go over well for this movie. Rob Morrow called me up, another call. I’ve never had this happen. Two phone calls from two different actors. He called me up also a few days before this, and he said, “Bob, you don’t know me. I’m playing so and so here and it’s a madhouse. It’s complete insanity. You’ve got to do me a favor.” I said, “What’s that?” He said, “Let me go home, please, let me go home. I’ll do anything. I’ll pay my own way. I’ll do whatever you ask me to, but please, I cannot work on this movie another second. It’s the most horrible experience I’ve ever had my entire life.” So here I am, confronted with all of this stuff, and I have a responsibility. It’s a $25 million movie and I’ve got to get it done and I’ve got corporate sponsors and the whole thing. And it’s another one of those things that a director has to do, a producer in this case, has to find compromises to just keep the baby alive.

CS: Incredible.

Shaye: Yeah. Anyhow, so it’s been a wild ride and as I’ve said to somebody recently, I’ve walked away from the table for a while, but I haven’t left the casino yet. And if somebody else that catches my eye and is fun and people don’t spit when they hear it, I would arguably do it again for the right kind of material. And in the meantime, I’m having a great time at Unique Features with a younger crew, who I can be a bit of a counselor for and a little bit of a possibly wise uncle, in a way, or experienced uncle, who can kind of give a point of view on filmmaking for the next generations.

CS: I have a final question and it is a really strange question, so bear with me. Years and years ago you did this movie “Book of Love”, which I did see. I’ve seen the movie. I saw it when I was a kid, I liked it.

Shaye: Oh good.

CS: But I’ve always been interested in this weird coincidence that that it was a movie about young people in the late 1950s, and I guess it was sort of autobiographical, a little autobiographical?

Shaye: Well, the reason I did it was because it was exactly the way I grew up in Detroit in the 50’s, and it turns out the guy who wrote the book, Bill Kotzwinkle, it was exactly the way, who’s exactly my age, and it’s the way he grew up in Scranton. So he was on the set most of the time and we were having more fun than anybody else. These guys were so good, that it was definitely autobiographical for sure.

CS: There is this interesting coincidence that in the same year, Joe Roth did this other movie called “Coupe De Ville”, which is a similar coming-oif-age film set around the same time period. And I was just like, how did two studio heads direct the same kind of movie in the same year?

Shaye: I don’t know. And I remember seeing that movie and being a bit scared that I was making a movie like it. I like mine better, but that wasn’t the point. And neither of us have gone on to have stellar directorial careers subsequent to that, either. But I guess there was something about growing up in the 50s that was hysterical and it was really halcyon times. And I guess it just dawned on both of us.

(Photo Credit: Getty Images)