Disney•Pixar invited ComingSoon.net to visit the Pixar campus in Emeryville, California in anticipation of Incredibles 2, and we had the chance to sit down for an exclusive 1:1 chat with legendary director Brad Bird! Check out the interview below, where we discuss with Bird the challenges of doing a sequel to such a beloved film, working on an accelerated schedule (the film moved up a year to switch with Toy Story 4) and which sequel landmines he tried to avoid.

RELATED: Watch the New Incredibles 2 Trailer!

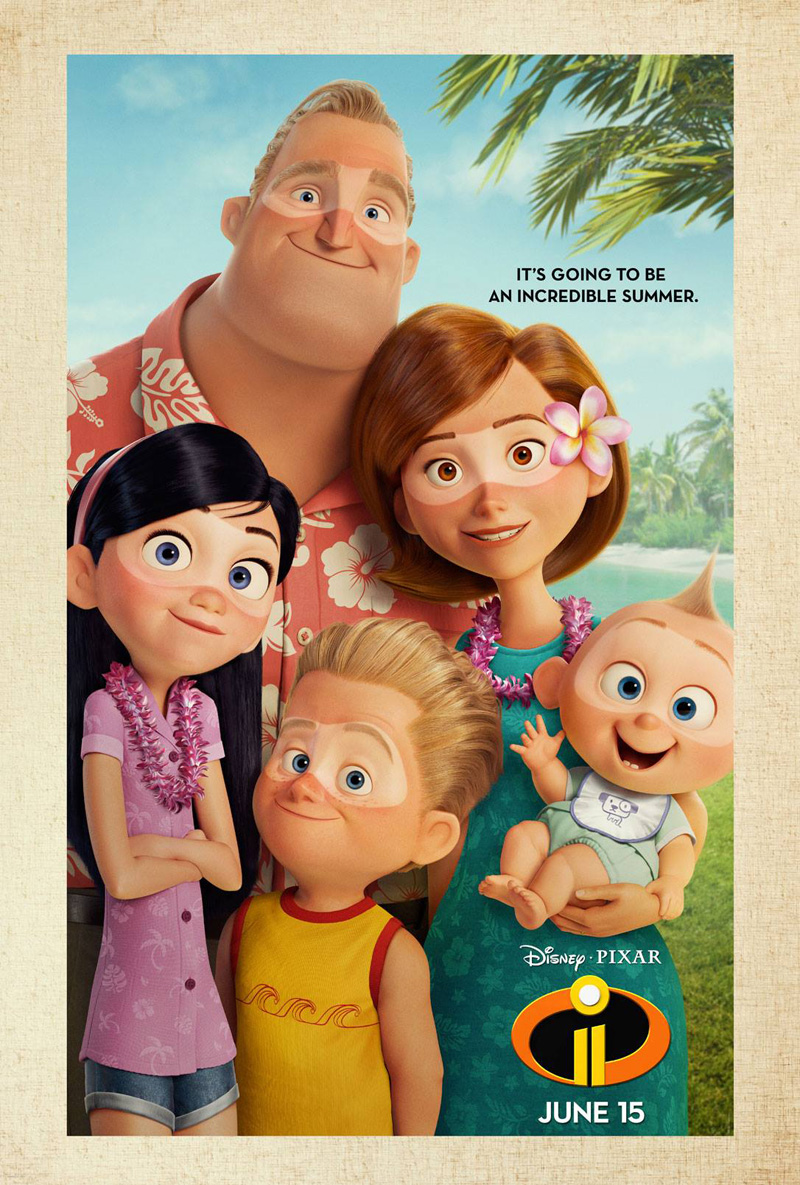

In Incredibles 2, Helen (voice of Holly Hunter) is called on to lead a campaign to bring Supers back, while Bob (voice of Craig T. Nelson) navigates the day-to-day heroics of “normal” life at home with Violet (voice of Sarah Vowell), Dash (voice of Huck Milner) and baby Jack-Jack—whose super powers are about to be discovered. Their mission is derailed, however, when a new villain emerges with a brilliant and dangerous plot that threatens everything. But the Parrs don’t shy away from a challenge, especially with Frozone (voice of Samuel L. Jackson) by their side. That’s what makes this family so Incredible.

The voice cast also includes Brad Bird, Bob Odenkirk, Catherine Keener, Jonathan Banks, Sophia Bush, and Isabella Rossellini.

Written and directed by Brad Bird (Iron Giant, The Incredibles, Ratatouille) and produced by John Walker (The Incredibles, Tomorrowland) and Nicole Grindle (Sanjay’s Super Team short, Toy Story 3 associate producer), Disney•Pixar’s Incredibles 2 busts into theaters on June 15, 2018.

ComingSoon.net: So it took you years to crack this story. What was the “eureka” moment for you?

Brad Bird: I would take a little bit of the issue with the way that’s phrased, because it makes it sound like I was just sitting in a room going, “If only! If only I could crack Incredibles 2, then I wouldn’t have to do these other films.” It was more like I had it in my mind, I had the idea of the role switch, and that Jack-Jack was going to be featured early on, and then I tried other things with it, and I was kind of idly thinking about it. But I’m idly thinking of five or six different things, so it’s not like I did other films because I was waiting to crack The Incredibles. It’s more like that was always in my mind, and I suddenly looked up and it was 14, 12 years later, and if I wait any longer, I’ll lose the opportunity, because nobody will remember the first film, or the actors will be too on in years, or involved in other things. It was actually really fun to get in there, but it wasn’t an intentional wait. It was just the way things happened.

CS: The first one came out right at the dawn of the superhero genre and since then it’s been overexploited and deconstructed and crossed over in every which way you could think of. How do you think “Incredibles 2” would have been different if it had come out in 2006 or 2008?

Bird: The quality of the animation wouldn’t be as good. [laughs] I was very proud that we did the first film with all the technical challenges we had, I’m amazed that we got it on screen and that our compromises were few. That said, the equipment and the animators and all of that has improved a lot, and it was really fun to go back with these characters and have people bring more experience to bear in putting them on the screen, because they’re the same characters but there’s a nuance to them now that I wish that we had on the first film.

CS: You planted the seeds for Helen’s arc in the sequel right at the beginning of the first movie, because she says to the interview, “I can’t see leaving superheroics to have a family—”

Bird: Well, the point of that— and I got a note from one of the Disney guys that goes, “That doesn’t track. Those don’t follow, because what they do in the movie is not that.” And I was like, “That’s the whole point. The point is that we think we think this, and we actually don’t.” So Bob says, “Hey, I’d like to settle down and have a family,” yet, when he has one, he kind of is going, “When am I going to be a superhero again?” Helen is going, “I can’t possibly slow down to have a family, now, I’m totally into this!” And she’s the greatest mother ever. Frozone is like, “I like to play the field, I’ll never get married! Chicks love me!” And then he’s got a very clear marriage going on by the time we’re in the film. So the idea was that nobody’s right about where they’re going in their life necessarily. You think you’re this, and you’re actually something else.

CS: Someone quoted you saying that the paint was still wet on the script when you began production. What were some of the biggest unresolved things as you embarked on it?

Bird: It was mainly the plot stuff. It was always changing. The plot part, the superhero part that we explored a lot of different ideas, and all of the ideas were interesting to me, and remain interesting to me, so if they didn’t serve the family emotionally… when you have a release date that’s fixed in space, and your time is always getting shorter, you can’t linger over decisions and go, “What if I tried it five different ways?” You have to go, “Not serving the movie. Out! Next!” So that’s the way it was kind of done, and every film has its own way of developing. I keep thinking, “Well, I’ve done one before, this will be easier for me.” No, it’s not. Even though you’re familiar with the game pieces, it’s a new chess game. You have different challenges. Every movie, I find myself adrift at the beginning of the movie, and then I find my way through the dark forest.

CS: For the first one, you drew inspiration from the Ken Adam designs of James Bond, and “North by Northwest,” and things like that.

Bird: You got “North by Northwest!” Good for you!

CS: Yeah. Film nerd!

Bird: I love the house in “North by Northwest.”

CS: What were some filmic references that you had this time around that were different from the first one?

Bird: I wish I thought about it that directly. I don’t know. I just know that I’m seeing a lot of movies, and they’re rich to me. I never try to do them straight across, like there was a scene in “Ratatouille” that was inspired by “Rear Window,” but the way it’s presented, no one would get “Rear Window” from it, but it was inspired by it. That’s where Remy is crawling up from the sewer and through the house, and seeing all the people and the lovers’ quarrel, and then he winds up on the roof. That isn’t like any part of “Rear Window,” but the idea of looking in on other people’s lives is, definitely. I was thinking of “Rear Window” when we went to that. It’s never a straight across thing, it’s usually the feeling that I’m after more than the exact shots or anything like that. You tell me! We’ll see what happens.

CS: What were some sort of sequel landmines that you wanted to avoid?

Bird: I think being predictable. Also, there is a tendency to increase the bombardment level of a sequel. Usually, people begin with very clear ideas of good movies, they begin with clear ideas about their characters, and then as they do sequels, they seem to forget the characters more and more, and try to out-spectacle. It’s because it’s easier to buy more gasoline to light and bigger sh*t to blow up and increase your effects budget than it is to make characters that people care about, but that is really the most important special effect, is creating characters that you care about. Then when you put them in jeopardy, people feel the effects much more. It’s kind of sensitizing people to the jeopardy rather than, if you just bombard, that’s good for the first ten minutes, and then it’s check-out time. The audience sits there with their mouths agape, and they don’t react. It just bums me when I see that, because you want people to be going, “Ooh! Ahh!” Or, “Hahaha,” or, “Whooo!” That’s what you want from an audience, and when they go into that slack-jawed, “Euhh,” I just hate it.

CS: Yeah, the catatonia.

Bird: The catatonia! I saw one film, and I won’t name which one it was, but it was a superhero film, where there was this whole row of people, it was opening day, the theater was packed, the film just blew up and blew up and blew up. And people just sat there like this. And when it was over, one of the guys, who didn’t react for the entire film, said, “That was awesome.” And I was like, “Well, if it was awesome, you would have reacted at least a little! Come on, man!”

CS: Speaking of special effects, you did two big live-action movies before this, and I know you did lots of junkets where people were like, “How did being an animator influence your live-action?” Well, how did your live-action experience integrate back into animation?

Bird: It’s kind of a version of the answer that I gave to all the people about animation. The only thing that helped me was going from hand-drawn animation into CG, because CG has the equivalent of lenses that you can swap out, you have sets, you have spacial relationships and camera moves through space, so it’s halfway to a live-action film. The language, you can get it even closer to live-action. But in terms of storytelling, it’s kind of the same gig. You’re trying to create characters, you’re trying to be clear, you’re trying to worry about pace and emotion and music and thrills. That’s the same. It’s just the means of getting them up on the screen. So the only thing that I would say that I learned was just going through two films and the problems that I faced doing those two films. I’ll have more knowledge, hopefully a little bit, after doing this, for the next film that I do, whether it’s live action or animation. So it’s just going through the process. To be honest, the process is still totally mysterious to me. I don’t know how anyone ever makes a good movie. It’s a miracle every time.

CS: When you were a student, you trained under the Nine Old Men, you were part of the Disney tradition. Now that a lot of the traditional 2D animation has gone away, do you think that there’s still a legacy of that knowledge, and that the people coming up after you are going to have the same basis?

Bird: Probably it’s not the same, exactly. I know that hand-drawn is strangely alive and well here, because Tony Fucile — who’s a genius animator that I’ve worked with on everything I’ve done in animation, except “The Simpsons,” but everything, he worked on my first film, he worked on “Iron Giant,” “Incredibles,” “Ratatouille” — he is not really that comfortable with a computer, but he is going over people’s work with a drawing thing, and they’re altering the work to match the drawings. He performed that function on “Inside Out.” Touching up, kind of saying, “If you lift this elbow, if you do this, it’ll read better.” It’s a hand-drawn sensibility, and it’s getting into this film. It’ all over this film. So it’s being kept alive in that way, but I would also say that hand-drawn animation is completely viable, and I think it’s very silly of the movie industry to disregard it. It’s just as powerful as an art form as any other form of animation, and I would love to see it really return, because it would be exciting to have many different kinds of animation in the family, and the marketplace.

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2 IMAX Poster

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Kyle Macnaughton, Philip Metschan and Shelly Min Wan. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Dean Kelly. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Tony Fucile. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Bryn Imagire. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Bob Pauley. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Bryn Imagire. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Dean Kelly. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Tim Evatt. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Tim Evatt. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Bryn Imagire. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Ralph Eggleston. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Garrett Taylor and Philip Metschan. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Ralph Eggleston. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

Concept art by Deanna Marsigliese, Matt Nolte, Bryn Imagire, Paul Conrad and Tony Fucile. ©2018 Disney•Pixar. All Rights Reserved.

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

\

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2

-

Incredibles 2