CS Score is back, baby! Apologies for the delay. The holidays ruined everything and delayed a bunch of interviews. But don’t worry, we’ve got some fun stuff coming in the next month or so, including an interview with the one and only Henry Jackman, composer of the upcoming drama Cherry and the Disney+ series The Falcon and the Winter Soldier.

For this edition, we’ve got a treat that’s just as delicious — an excellent interview with composer Ilan Eshkeri, who talks about his work on David Attenborough’s A Perfect Planet as well as his excellent score for the video game Ghost of Tsushima. We’ll also take a look at Waxwork Records’ vinyl release of Edward Scissorhands and review Intrada’s re-release of Alan Silvestri’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

Let’s do this thing!

News

Finally it’s back! We have 500 units of the #HarryPotter #JohnWilliams #Soundtrack Collection (7-CD set) coming back in stock! Order now at https://t.co/M4LZNDtqCp They’ll be shipping out later this month! @MuggleNet pic.twitter.com/r4z93uKfbt

— La-La Land Records (@LaLaLandRecords) February 2, 2021

Available to order now at https://t.co/M4LZNDtqCp – world premiere full #soundtrack score release of #HardRain by #ChristopherYoung – Limited Edition CD release of 1000 units! #ChristianSlater #MorganFreeman #90s pic.twitter.com/6kPYMueQKX

— La-La Land Records (@LaLaLandRecords) February 2, 2021

Back in stock! PATTON and CHINATOWN. Two classic scores by Jerry Goldsmith. https://t.co/YFQ8wlDAdz

— Intrada (@IntradaCDs) January 30, 2021

Review

Edward Scissorhands

Danny Elfman

Say what you will about Tim Burton, but his patented (some would say overdone) gothic schtick always brings with it a wonderful score by Danny Elfman. The duo have collaborated on 16 films dating back to Pee Wee’s Big Adventure. And while their more recent work hasn’t quite reached the same level, the pair absolutely dominated the late 80s/90s with films such as Beetlejuice, Batman, Batman Returns, Mars Attacks!, Sleepy Hollow, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas and, of course, Edward Scissorhands.

Edward Scissorhands stands as the most impressive of Burton and Elfman’s collaborations. The haunting vocals and bouncy circus-styled rhythms have remained an Elfman trademark, appearing in his scores for Spider-Man, Sleepy Hollow, and Burton’s Frankenweenie, but here sound fresh and unique. Indeed, there’s a feeling of tragedy permeating throughout Scissorhands that occasionally threatens to overtake the more whimsical aspects of the score, but Elfman always pushes against the darkness with powerful bursts of enchantment as heard in the famous track “Ice Dance.”

The soundtrack is divided into two parts, “Part One: Edward Meets the World …”, which opens with the terrific track “Introduction (Titles)” that plays over the opening credits. Said track introduces the first of two themes Elfman employs for the album, with Theme A best described as a waltz coated with the aforementioned choir. Theme B, or the Love Theme, makes its first appearance in “Storytime” and appears briefly throughout Part One before Elfman lets the theme take center stage in “Ice Dance.” The remainder of Part One segues between lighter fare, such as the track “Edward the Barber,” which features a fun and plucky violin solo as Edward uses his talents to reshape the lawn hedges throughout the neighborhood; and the bouncy, rhythmic “Cookie Factory” that utilizes many of the same zany aspects heard in Nightmare Before Christmas and Pee Wee’s Big Adventure.

Naturally, Burton’s film takes a much darker tone in its final act; and Elfman’s music follows suit in tracks such as the aggressive “The Tide Turns (Suite),” which sounds very Batman-esque and even features the same driving rhythms heard in “Attack of the Batwing” in Batman. The action continues in “The Final Confrontation” before the music dips back into melancholy with “Farewell.” “The Grand Finale” segues back and forth between the soundtrack’s two themes before exploding into a truly enchanting rendition of the Love Theme that plays out over the film’s closing credits. The soundtrack closes with the Tom Jones song “With These Hands,” which feels ridiculously out of place but doesn’t hamper the experience too much.

Edward Scissorhands remains Elfman’s magnum opus, an astonishing score that delights, haunts, and captivates the listener with each and every track.

As a side, in a 2015 interview with Vulture, Elfman spoke of his score for Edward Scissorhands and offered some insight into his creative process, or lack thereof:

“I’ve always enjoyed using some kind of choir, or the boys’ soprano soloist; there’s just something about the sound of children that particularly gets me.

There was nothing to indicate what music should be played for this movie. I had two themes for Edward Scissorhands but no themes for anybody else. That’s just the way it came together.

Frequently, my process isn’t really a process. It’s what scenes form in front of me and trying to explain it. I don’t know what made me want to use children’s voices other than telling the story and telling the fairy tale. I think that probably opened the door to Tchaikovsky and using a choir in that way, I’m sure. But it’s all very unconscious.

Edward was a really cool process of being left alone with Tim. Nobody was watching over our shoulders, nobody even seemed concerned that we were even writing a score or working on the music. We were just two weird guys working on our own, under the radar and everything.

And the result was Edward.”

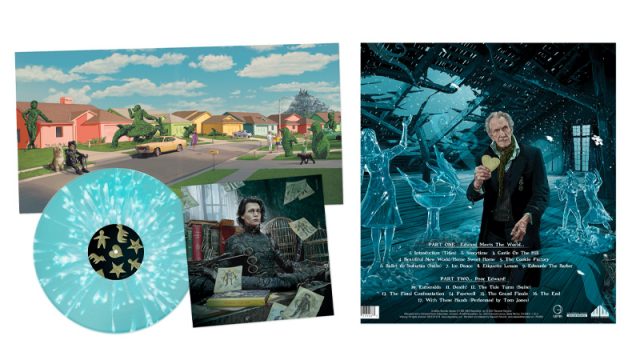

So, why bring up Edward Scissorhands now? Well, the folks over at Waxwork Records saw fit to repackage the original motion picture soundtrack with the 30th Anniversary Deluxe LP, replete with new artwork by Ruiz Burgos, a 180 gram “ice sculpture blue with snow splatter” color vinyl, and re-mastered audio for vinyl from the original masters.

Here are some shots of the set:

Currently, the record is sold out at Waxwork Records, but keep your eye out for this gem of a release; and get your hands on it as soon as it becomes available once more.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit

Alan Silvestri

Alan Silvestri’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit? is not for the faint of heart. The score zips along like a wacky cousin to Back to the Future, replete with the composer’s signature driving rhythms and action gusto, albeit in a much loonier fashion. In other words, if you dread “Mickey Mouse” cartoon music then you best steer clear of this release.

For those who can stomach the madness, Who Framed Roger Rabbit? stands as one of Silvestri’s crowning achievements, expertly blending elements of film noir with the zaniness of those classic Looney Tunes shorts featuring Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and others.

For years, Silvestri’s score remained one of those hard to get releases collectors desperately had to search for on eBay. Thanks to Intrada, the soundtrack was re-released as a 3CD set featuring nearly all of the music composed for the film in the original manner it was intended. Linear notes explain that nearly every cue was tweaked with in some way and either repurposed, shortened, mixed with other tracks or cut altogether. In this case, the results aren’t entirely noticeable in the film, but this amazing presentation of Silvestri’s work offers a unique insight into the composer’s thought process.

The soundtrack commences with the wackiness right off the bat with the Maroon Toon Logo theme that pays tribute to Carl Stalling, who, a quick Google search reveals, produced a new score for Warner Bros.’ animated shorts once a week for 22 years — #legend. More wackiness ensues in the track “Cartoon,” which plays over the Roger Rabbit/Baby Herman short that opens Robert Zemeckis’ film. Things slow down with “Valiant & Valiant,” a somber track dominated largely by trumpet and piano before a bell toll ushers in the appearance of “Judge Doom” along with a bit of sinister music that accompanies Christopher Lloyd’s genuinely terrifying villain and continues into the track “The Weasels.”

“Strange Bedfellows” closely mimics the sound Silvestri employed for Doc Brown in Back to the Future, but also introduces a recurring motif heard in the various action cues spread throughout the score — in his Movie Music UK review, writer Jonathan Broxton describes this music as written with “a spiky, insistent edge that makes use of oddly-metered rhythms, woodwind trills, and clattering xylophones in the percussion section. One particular recurring motif moves through much of the action music, a sort of tremolo effect which is first heard in this cue on flutes, before shifting to strings at the 30 second mark.” This is one of the score’s most exciting aspects — I genuinely love Silvestri’s action writing here, especially as its played more aggressively with percussions later in the soundtrack in tracks such as “Got Ya, Kid,” where it’s accompanied by drums, bells, and heavy brass. (“Got Ya, Kid” also employs plenty of wild jazz to go along with the action, which works surprisingly well.)

“Toon Killed My Brother” and “Have a Good Man” are shorter tracks that feature the softer “love” theme of the pic, while “R.K. Maroon” goes full jazz and segues from playful to dark and sinister to moody blues and back again at least a dozen times.

Then we get to another big action cue, the track “The Getaway,” which delves into a western-ish fanfare before presenting the aforementioned action motif once more. This track paves the way for “Toontown,” a lengthy 6-minute bundle of wacky action score that really encapsulates the enormity and insanity of Zemeckis’ film. It’s a wild track, for sure, but one of the most exciting pieces of music found on the entire album.

More zaniness ensues with “The Kick/The Climbing” before the film comes winds down with the track “Saved” and closes with “Big Kiss/Smile, Darn Ya, Smile” and “End Credits — Roger Rabbit Medley (Film Version).”

This 3CD set doesn’t stop there. Also featured are alternate takes of various tracks and even bonus cues from the short films “Rollercoaster Rabbit” and “Trail Mix-Up” by Bruce Broughton and “Tummy Trouble” by James Horner. The original 1988 soundtrack album is also presented here for those longing for more compressed cues.

All told, Who Framed Roger Rabbit? is a classic film score bursting with energy and playful themes made during a time when Silvestri was at the top of his game; and this Intrada presentation is the only way to fully enjoy the composer’s masterwork.

Purchase at Intrada by clicking here!

Ilan Eshkeri Interview

ComingSoon.net: What drew you to Perfect Planet?

Ilan Eshkeri: Well, that’s a great question, because it wasn’t simple for me, you know? This is my fourth project that I’ve done with David Attenborough over the years. And so, in some ways I’d already scratched the David Attenborough itch, if you know what I mean? I’d had the privilege [of working with him] before and so there needed to be something about it that drew me to it. And the most important thing was what the project was about because we are in such a dire situation right now in terms of the planet. And I see myself with my daughter talking about this — she’s five, but I realized that I’m teaching her to recycle. I’m teaching her about sustainability. I’m teaching her not to waste food, but as a kid who grew up in that late seventies, early eighties, we didn’t talk about those kinds of things.

And it seems to me that that there’s something really important happening with teaching the next generation of children to see the world in a different way, to see the world as a place that we’re part of, that we contribute to as much as we take from. Whereas in the past the world was just something that we use for our own benefit. And the children that are growing up now, they’re going to be the next world leaders, the next business leaders, the next scientists, the next doctors; and out there on their call, they’ll have a different way of perceiving the planet than we do, and that’s really important.

So, when I started talking about this program, I thought this is a chance for me to expand upon that feeling into my work and try to, in my own small way, through music, educate a wider audience into the same way that I’m thinking, which I think is extremely important. So, that was really the guiding desire.

And the other thing was, I remember going into the production companies in Bristol, which is outside of London. It’s a two-hour train journey and I really thought about it on the way there. I went into the meeting and I said, “Look, normally the way that these series are done, it’s a very symphonic, classical approach. And I don’t want to do that. And if you want that — don’t hire me! What I’d like to do is I’d like to take a more contemporary approach to it.” And, the production was really into that. Actually, the whole way through the project, the production team were very, very generous with their belief in whatever idea I threw at them. Not all of the ideas stuck. We worked through a lot of music, but I believe that we brought musically a different approach to the series.

CS: Do you find a project of this magnitude — where you’ve got so many things happening throughout the course of the film — daunting?

Eshkeri: Yeah. It’s always daunting. Doing a job like this, and like I said, I’ve done some like this before — so I kind of knew what to expect — but it is daunting because normally when you write a TV series or film you have to write a few themes — you have to write a good guy theme, a bad guy theme — whatever — the love theme — I’m stereotyping here, but you know what I mean? You have a handful of themes you have to write. But with this, it’s like writing 45 short films because that’s what it is. You meet these snub-nosed monkeys with blue faces, and they’ve got a theme, and then you meet some ants, and they’ve got a theme, and then you meet some penguins, and they’ve got a theme, but each of the stories of these animals is encapsulated in a three to five-minute sequence.

And then I’d look at the sequence and I’d say, okay, well, this is like a heist, this scene is a tragic love story, this scene is like a horror movie, you know, whatever it is. I discussed that with the director, and I’d work out what it is. And yes, it was like writing many, many short films. So that bit of it is daunting. But what was really important to me was — when I’ve watched the series in the past it seems to me that the music just rolls. It goes on from a sequence where you meet this creature and then it goes onto the next creature and the next creature after that, but there isn’t an anchor and I really wanted to write a theme that’s the front title, end title, and also comes in between all the sequences so that you have an anchor that keeps bringing you back. And this was the theme that I wrote, it’s called “A Perfect Planet,” which for me is the Earth theme, the Mother Nature theme. It has voices, and it has these very simple, moving arpeggio string lines, sometimes a bit of piano, something that really connects easily with the soul somehow.

The whole idea that we discussed at the initial meetings was that this is a celebration of the planet. This is an opportunity to see how beautiful it is. There’s a whole episode on volcanoes — volcanoes are normally the bad guys, right? Well, not in this series. Volcanoes give us life. They’re the fundamental, the basic — where it all begins. And so, the whole idea was to make this a celebration. And then in the final episode, that’s killer episode where you then see — oh my God, we’ve had this perfect place, and this is what we’re doing to unbalance it. That’s really worrying, but also this is what we could do to help and make it better.

CS: You’ve worked on a number of David Attenborough projects. Have you ever met or interacted with him?

Eshkeri: I have met David on several occasions on the projects I’ve worked on, but on this one, the vast majority of this project was done during lockdown. So, David, being in his nineties, wasn’t leaving his house. So, there was no opportunity. I didn’t get to meet him or interact with him. I do know that when he records the voiceover, which he did in his living room, they brought a truck to his house and passed the cable through a window and he recorded it there in his living room. When he records the voiceover, I know they play the music to him. And I know from my previous experiences with him, he loves music and he is opinionated about music. So, I think if he had a problem with it, I’m sure he would say something.

My memory goes back to the first project I ever did with him. And on that project, we were recording in Abbey Road Studios and he came, and he spent the morning with us on one of the days. And then he left. I mean, it was such a privilege to have him sat next to me in the control room to discuss the music — he’s a very capable pianist. He can read music and he knows music. So, it was brilliant. It was lovely to have him there. Then he left and I went out onto the floor at Abbey Road Studios, you know, where they recorded Star Wars and Harry Potter and a thousand film scores that we grew up watching.

So, I went out there to just say a few words to the orchestra about what we were going to do next before the lunch break. And as I got up into the conductor’s podium, out of nowhere a butterfly came and landed on the stand — this was November! It was freezing cold outside; and as you probably imagine, there was a lot of doors between the recording studio and the outside world. It’s not easy to get into. How on earth was there a butterfly in there from the recording studio? It was really an extraordinary and very magical moment. I like to think that David somehow released it into the studio.

CS: You’ve written scores for films such as Stardust and Kick-Ass, and you recently did the video game score for Ghost of Tsushima, which I just beat by the way — and, for the record, loved your music —

Eshkeri: Which ending did you choose?

CS: I spared the uncle.

Ilan: Go back and do the other ending because the music when he kills the uncle is much, much more emotional. I would definitely, from a music point of view, definitely want to go that way.

CS: Absolutely! I’ll have to go check that out. And that goes with my question, because you’ve discussed the difficulties of scoring a documentary … do you face the same challenges with video games? Or is that a completely different beast altogether?

Eshkeri: Absolutely. But it’s a different discipline. I mean, there’s very few situations in the video game — well, I’ve only done two video games, the Sims and Ghost. The only place where I had to write two alternative things was that moment [in Ghost]. So, there wasn’t a lot of repetition like that.

I’ll say two things about this. The discipline of writing a video game is different because you need to write music that works in layers. And so, if you take some of those layers away the music still works, and if you put them all together it still works. That way you get these different intensities of music, so you can play and as you’re fighting, it gets more intense or less intense depending on what you’re doing. But that’s because there’s drums all the way through, but they only come in when certain things happen or however the construction of the interactive element of the game is conceived. And it’s really useful if you know that, because then it becomes a tool that you can use, right?

Every discipline has its own set of rules, its own way of interacting with the audience. And you have to bear that in mind when you’re writing it. So, with a video game, what that means is that sometimes with your violas or the bits that are normally hidden in the orchestra, you can just hide them. They don’t work so hard. With something like Ghost, when I was doing the taiko drums, I was like, well, this part could just be on that side. So, you’ve got to really write the shit out of those taiko drums … you’ve got to really make sure that viola part that normally nobody would hear and would normally just be filling in the gap in-between the violins and cellos — no disrespect to the brilliant viola players — but suddenly you’re like, well, what if that was the top line? What if that was the bit that everyone was hearing? So, you’ve got to write every line of music like it might a solo. And so that is definitely a unique challenge about video games.

The other thing that I would say about it though, is that in every other way it’s exactly the same as doing anything else because it’s just the latest iteration of the oldest form of human art. In Australia, they just found the oldest cave paintings — older than anything they found before. There were these drawings and these handprints; and those cavemen all those tens of thousands of years ago, what were they doing? They were telling a story through art, through the creation of something. And then people sang songs and they told stories through singing songs and then they act out things and they told stories through acting and performing and theater was born; and then opera and then ballet … all these different ways of telling stories. Then one day somebody creates cinema. Then one day somebody creates video games, and video games are just the latest way in which human beings are enjoying telling stories. And so on that level, if you’re writing music that is describing an emotional narrative, which is what I do, then the job on that level is exactly the same.

CS: That’s interesting. In the case of Ghost, it feels like a movie; and your music drives the plot and the story and the action.

Eshkeri: Well, the plot is incredible! I was very reluctant to take on the project, because I was like, it’s like a samurai slicing up some people — it’s blood and fighting. I don’t know what I’ve got to say about that. I don’t have a moral point of view on it. I have a creative point of view on it. I’m like, I don’t have anything emotionally to say about that. I didn’t really want to do the project, but I went out and they politely did the meeting with Sucker Punch and I walked out of that meeting completely speechless. The story is compelling and it’s a story of the ages. It’s a story about how we accept the past that our forefathers gave us whilst trying to forge a new way with the future. I mean, every generation has wrestled with that particular emotional battle. And this was a very rich place from which to write music.

CS: That’s interesting that you’d say that. I grew up listening to James Horner and he would talk about how he always scored the emotional beats of a film — especially during the action scenes.

Eshkeri: I absolutely adhere to that! My mentor Michael Kamen said that as well, because you know music does the job words cannot fulfill, right? That is the point of music. Music can express something that sometimes words can’t, and music is all about emotion. And so absolutely even in the action sequences. I mean, you can write action for the sake of action. But it gets tedious. What is my character feeling in that moment? It’s all about the emotion. Absolutely. Your job is to tell the emotional narrative. Absolutely.

James Horner is a huge hero of mine that I grew up listening to his music. What a tragedy that he left us so long before his time. But yeah, I one hundred percent agree with that idea. I think, whether I was scoring a cave painting or the latest computer game, that the same principle would be there. I would look at what was on the screen and I would say, what is this person feeling and how do I translate that into music?

CS: Do you have any other projects coming up that you can talk about?

Eshkeri: Absolutely! Around the time that I was doing ghost, in the summer of 2019, I had finally brought together, after years of work, this project called Space Station Earth. It’s a film, which I’ve directed and written all the music for; and I did it in collaboration with the European Space Agency, which is our version of NASA, and the astronaut Tim Peake, who contacted me — he was a fan of my music — and before he went to the international space station, he asked me if I would do some music for him. I was so inspired. I went to meet him at Johnson Space Center, and I was so inspired by the time we spent together that I thought, why are we just making one short thing? Why don’t I make like a big, long film and tour it like a live show?

So, the film is a live show, a live show of images of space, the astronauts traveling up to the space station … and it’s just music that accompanies it; and it ties in nicely with your previous question, because I thought there was so many documentaries explaining about the International Space Station, interviews with astronauts; but the astronauts, they all share this unique experience of — you know, there’s only been 550 or so astronauts — and all of them, wherever they are from the world, share this thing. Some people call it the overview effect, but it’s the experience of being physically off the planet and looking down on it. It’s a life-changing experience, and I really wanted to try and express the journey and that experience, because words … there aren’t enough words to describe it. Could I express that through music?

We got to do our first performance in Stockholm, and we had a satellite link up to the International Space Station. It was very exciting. And 10,000 people turned up to see that. It was a free concert in the square in Stockholm, the main square; and 10,000 people turned up to see it and to see a couple of astronauts chatting away and talking to the commander of the space station live. And then we came up and I was really nervous. I was like, this is very risky. It’s like three screens of images and just us playing music for an hour. How’s that going to go down? I don’t know. There’s 10,000 people here and I thought by the end of this there’s going to be 10 people standing in front of me. But actually, they all stayed. Ten thousand people started there, and 10,000 people applauded at the end. It really was great.

We had already had plans to do a bunch of touring around Europe, but then the pandemic hit so that all got put on hold. You know, we were going to play Glastonbury. I had all these festivals lined up. It was amazing. But anyway, so all that got put on hold. Now, as of January, we have put all these plans back together, and I’m not really allowed to say what’s happening yet, but keep an eye on my social media and there’ll be some updates very soon about the tour for my show Space Station Earth.

For more info about Ilan’s upcoming tour or any of his works, visit: ilaneshkeri.com. Follow him on Twitter @ilaneshkeri and Facebook @IlanEshkeri.