Director Ted Geoghegan on his new thriller Mohawk

Dark Sky Films will release Mohawk theatrically on March 2, with a simultaneous VOD and HD Digital release, and ComingSoon.net had the opportunity to talk to director Ted Geoghegan (We Are Still Here) about the Native American revenge thriller (currently at 94% on Rotten Tomatoes). Check out the interview below, in which we talk about the making of the film, representation in Hollywood, his next supernatural project and, of course, Batgirl.

After one of her tribe sets an American camp ablaze, a young Mohawk warrior finds herself pursued by a contingent of military renegades set on revenge. Fleeing deep into the woods they call home, Oak and Calvin, along with their British companion Joshua, must now fight back against the bloodthirsty Colonel Holt and his soldiers – using every resource both real and supernatural that the winding forest can offer. The film unfolds over the course of one bloody day during The War of 1812.

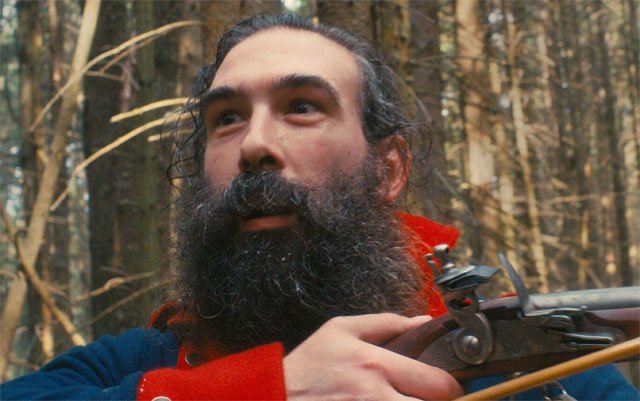

Mohawk stars Kaniehtiio Horn (Hemlock Grove), Justin Rain (Fear the Walking Dead), Eamon Farren (Twin Peaks: The Return), Noah Segan (Looper), Robert Longstreet (I Don’t Feel at Home in this World Anymore), Sheri Foster (Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt), Ezra Buzzington (Justified, The Middle), Ian Colletti (“Arseface” from AMC’s Preacher) and Jonathan Huber (WWE Superstar Luke Harper) making his big screen debut.

Geoghegan directs Mohawk from a script by himself and Grady Hendrix (author of My Best Friend’s Exorcism). Travis Stevens and Greg Newman produced.

ComingSoon.net: Were you pleased with the reception at the premiere here in New York?

Ted Geohegan: Yeah. It seemed like people responded to it in the right way. It was what I was looking for, so, yeah. It’s that sort of thing where the people who don’t respond to it as I hope usually do so because of their own baggage that they bring into it. I’ve had a few friends come up to me, like, “Hey man, I saw ‘Mohawk.’ It’s not really that scary.” It wasn’t supposed to be. It’s kind of this sad-angry drama. It’s a horror movie in the same way that I wake up every day in the horror movie that is 2018.

CS: That was what was strange to me, I heard some mixed things coming out of Fantasia Fest and I guess there were certain expectations after “We Are Still Here,” but I just took the film at face value. I wasn’t coming in being like, “Oh, I hope there’s frickin’ ghosts.” You set out to make a Native American revenge thriller, and that’s what you made.

Geohegan: It’s my political stance. My political party is that movie.

CS: I don’t know if you’ve faced any kickback on this, but a year ago everybody was super excited because Joss Whedon was gonna direct a “Batgirl” movie, and everybody went, “Oh, yeah, the ultimate feminist director is gonna make a Batgirl!” Cut to a year later, we’ve had Patty Jenkins do “Wonder Woman,” Ryan Coogler did “Black Panther,” and there’s almost this expectation that if you’re a director making a film about a certain culture or gender, that you have to be part of that culture or gender. Have you faced any kickback as a super, super white dude?

Geohegan: I’ve been very grateful insomuch as the Mohawk nation has been very supportive of the film, and I made it a point at all of our screenings to make sure that we are as transparent as possible about how humbled we are to be telling this story. And our lead actress, Kaniehtiio Horn, who is Mohawk, was a huge part of why this film was made. From day one, I have said we’re seeing more and more Westerns these days, there’s more and more films set in earlier times, but Native Americans are being portrayed by anyone of color, like, “Oh, we’ve got a few Latino people, they can play the Native Americans in this film.” Unfortunately, the Native American populace is very small, and that’s due to the atrocities that have happened over the past several hundred years, so yes, the pool is smaller, there’s just no other way around it in terms of viable Native American actors, but they are out there. The fact that Kaniehtiio was so receptive to the project and was able also to address her community and bring members of her community into the film in terms of things like the language — the characters in the film speak Kanien’kéha, the Mohawk language, and that was a huge opportunity that I never saw when creating the script, to actually have someone show up and say, “Oh, I can speak Mohawk, let me show you how this line would sound,” and hear it, and suddenly be like, “Oh my god.” This is the reason why, even if you are not the party in which you are telling this story about, it’s so important to make sure that you have people from those groups involved, to make it as accurate and poignant as possible. In the case of Kaniehtiio, I co-wrote the script with Grady Hendrix, who is also a white guy of European ancestry, and when we sent the script to her, she read it and said, “You guys really did your research, I’m really impressed by the fact that the film feels so authentic, but there are a lot of things in it that are not Mohawk,” and we jumped at the opportunity to have her insight. Every single thing she could tell us, we took to heart and put into the script. I feel like it is made with as much love and respect and humility as a project could. I look forward to the Native community hopefully appraising the film and seeing what we were attempting to do with it.

CS: To piggyback off of that, as a director, how do you feel about that current push towards seeing more representation behind the camera as well as in front of the camera?

Geohegan: I’m all for it. I feel completely humbled that the Mohawk community has embraced a film called “Mohawk” that was written and directed by a white guy. I sincerely hope to see more Native, First Nations, or aboriginal people being put into the forefront not only in front of the camera, but behind it. I recently heard about some film forums that are happening, both in the U.S. and Canada, with the intention of fostering Native writers and directors and trying to get their projects off the ground, and I will do everything in my power to be a part of that if they will have me, because I have learned so much about myself by making this film that I will not pass up the opportunity to give back to the community that we portrayed in the film.

CS: You’re also a publicist, and you work on a lot of different kinds of movies. In terms of the industry at large, not just for this film, there’s a little less acceptance for, say, a Joss Whedon doing a “Batgirl” when there’s X number of capable women who could also do that. How do you feel about that?

Geohegan: The truth of the matter is, whenever a film gets announced, whenever a film is conceived in any capacity, my first thought is, “I hope the right man or woman gets the job.” After that, I think about the potential to be able to amplify certain voices, and sincerely hope that those projects are given to people who will be capable of doing that. But the fact that we have Jordan Peele doing “Get Out,” or Ava DuVernay doing “A Wrinkle in Time,” I don’t want to say we have bigger opportunities, but there are these amazing occasions for people of color, for women, for all these marginalized people, who we haven’t heard their voices in cinema — either ever or in a very long time — suddenly to be telling these stories. The bottom line is, when I say I hope they pick the best man or woman for the project, the best person for the project, I think that we’re starting to see a revelation in the industry of people going, “The right person for this project is a Native person, is a woman of color, is anything,” and I think that we’re opening our eyes a bit more, and we’re seeing situations like with Joss Whedon and “Batgirl,” where they say, “Oh, no, I really think he’s the best person for the job.” It’s like, “Really? You can’t think of one geek girl out there who couldn’t run circles around this guy?” I like Joss Whedon, I think he’s a cool guy, but you’re really telling me that, out of literally everyone on Earth, that’s the best person to tell the story of a woman finding her inner warrior? No. Let’s dig around here. And I’m fully aware of the fact that I just directed a movie about a young woman finding her inner warrior, and again, I go back to the statement I made earlier: I’m wildly humbled to have been granted the opportunity to tell this story, and I hope that I, a white man who has never felt marginalized in his life, can use the opportunities that I’ve been given to help amplify voices such as women’s stories, such as the LGBT community, such as Native people. These are all groups that I myself want to see represented in film as much as possible, and whether that means that I’m directing it or whether it means that I’m helping somebody do that project, whatever I can do to make that happen, I want to make it happen.

CS: Let’s go back a little bit. The road to this movie is also kind of interesting. You did “We Are Still Here” for Dark Sky, and that was a big success for them, correct?

Geohegan: Correct.

CS: They immediately wanted a second film from you, but it wasn’t initially this film. Can you talk a little bit about “Satanic Panic,” which was formally announced in a press release but then sort of quietly went away?

Geohegan: After “We Are Still Here” I had the opportunity to work on a number of projects, all of which were very similar to “We Are Still Here,” some thematically, some visually, some in the vague supernatural element. While I love haunted house movies, I didn’t want to be the haunted house guy, and wanted to do something extremely different. I had conceived of a project with Grady Hendrix, a dear friend of mine and a bestselling author, and that project started moving forward, and in the midst of it, I was given the opportunity to tell a story that was wildly different from “We Are Still Here,” and we jumped at the opportunity to be able to tell the story that was so much more different. Essentially, it’s that I wanted to make a film that was as hard of a 180 as possible from “We Are Still Here,” and the project that Grady and I initially were working on was thematically very similar. When the idea and the opportunity to make “Mohawk” with Dark Sky became a reality, I leapt at the opportunity to tell that story. Given our current political climate, I felt as though this was the proper story to be telling at this time.

CS: It is definitely much more of a hot-button film than a standard horror flick. Once you brought Grady in, he’s a self-described War of 1812 fanatic, so in what ways did he and his knowledge help hone the project during the writing stage?

Geohegan: I knew at a very early point that I wanted to tell this story about the Mohawk people during the War of 1812, during which time the Mohawk as well as lots of Native American tribes of the Northeast decided to remain neutral, but they themselves, during this time of neutrality, were being utterly decimated by the new Americans. To me, that felt like such a specific allegory to what’s going on right now with marginalized people. I couldn’t pass up the opportunity, I wanted to tell a story of people who said, “We’re being screwed over, we’re going to just keep our heads down.” And then it’s like, “Even keeping our heads down isn’t helping, nothing is helping, we need to strike back.” I brought that concept to Grady, who, with his factual accuracy, was able to help me craft a story in which that scenario was 100% historically accurate. Grady’s also, if you’ve ever read any of his books, he has a knack for voice. He was integral in helping every character in the film have their own voice, in terms of how they spoke given the era, in terms of differentiating all these people. “Mohawk” is an ensemble film, with 10 characters in almost every scene of the film. There are very few scenes that feature just one person, so when you have that many people sharing the screen at once, it’s so important to be able to say, “Oh, there was this guy, and there was this guy, and there was this guy,” especially when they’re all wearing the same clothes. Grady really helped flesh out those opportunities, and through it all, helped keep the entire thing 100% historically accurate.

CS: Knowing Grady and having read some of his books, and knowing you… you guys are both very funny guys. This movie, even though it has moments of levity, is pretty serious. Do you feel in a future film you guys might want to tackle something with a little more humor?

Geohegan: Absolutely, and the project we worked on shortly after “We Are Still Here” is extremely funny. It’s definitely a lighthearted, gory romp. But given the enormity of the topic we were discussing, we made the decision very early on to have a story with minimal humor. We’re telling a story about the decimation of a native people, we wanted to treat it with the respect and the gravitas that it deserves.

CS: The first two-thirds of the film takes place in the woods. There are no sets until you get to the third act. It has this feeling of, whether intentionally or not, of kids playing in the back yard, because of that minimalism. Was that something that you kind of embraced while you were making it?

Geohegan: When we shot the film, it was shot on county land outside Syracuse, New York, and we worked with the Onondaga Film Commission there, who had taken us to several locations, and said, “What do you think about this, what do you think about that?” As we looked through them, we made the conscious decision — I mean, the forests always kind of look similar. Anywhere, the forest can look the same. And we came up with the idea, on every scene, let’s try to starkly contrast the scene before it, but bearing in mind that the forest can only have so many looks. There’s only so many ways that you can paint the forest. So we made it a point throughout the whole process to just constantly be changing it up, every chance we got, to do something that felt slightly different, but similar enough that there is a concern that these characters are running around in circles. We wanted it to feel like, “Wait a minute, the bad guys are in this location. Is this the same location that our heroes were just in? Are they closing in, or is it completely different?” Given the fact that we had to drag ourselves an hour out of Syracuse and then another hour deep, deep, deep into the woods, we made it a policy that every time we set up shop, is there any way that someone could say, “We shot this in someone’s back yard.” And if it was, we had to find a new angle. We were constantly ensuring that there was depth of field, that we were aware of the fact that the shot went on forever, or that we could sweep around and see, in a 360 vista, that they’re in the woods, there’s nothing around them in any direction. These were things that were important to us, so while it may feel like kids playing war in their back yard, we wanted to do our best to ensure it didn’t look like literally like kids playing war in the back yard. When you’re working on a limited budget, we made certain creative decisions that we were very excited about, such as shooting with all the natural light, which was the decision that our director of photography, Karim Hussain, made. Films are not traditionally shot in natural light, and it gives the film a very specific, very bright, almost neon look. It was something that we felt would differentiate our film from other period pieces, other films set during this time. We never set out to make diet “Last of the Mohicans.” When you have a specific budget -and period pieces, especially films set 200 years in the past, are typically shot for tens, if not hundreds of millions of dollars- you come up with, even in the scripting stage, ways in which to tell a story that’s quite grand in a way that’s also intimate and appropriate for the budget that’s being spent on it.

CS: It never looked like a War of 1812 recreation society or something like that. It always had a certain element of realism to it. I like that it felt very earthbound as opposed to a big, lavish Hollywood production with lots of big sets. In a lot of ways, the film it most reminded me of was something like “The New World,” which spent most of its runtime in nature.

Geohegan: Yeah, it doesn’t rely on a lot of the conventions that would be in a film like that. With “Mohawk,” another creative decision that Karim had made that I was really excited about was the fact that the camera is very, very stationary, it’s almost like on a tripod. It’s very, very still, until the first gunshot. And at that point, the film becomes almost exclusively handheld. Handheld cinematography is something that one usually doesn’t see in a period piece, in and of itself, it feels so modern, and it gave us the very unique opportunity to be able to shoot this film in ways that people might not traditionally expect. From day one on this movie, similar to what we were saying earlier about being given the opportunity to tell a story so different, was, if we’re gonna tell a story that’s different from “We Are Still Here,” we’re going to tell something that is wildly different, let’s embrace that “wild” part. Let’s do something that’s really outside the box. Hopefully it still embraces the genre fans, and even fans of historic dramas. I want people of all ages and identities to be able to sit down and enjoy this film.

CS: What do you have next on your plate in terms of features?

Geohegan: Right now, I’m currently writing two screenplays, neither of which I’m going to be directing, for different projects. And I have a project I’m very excited about that hopefully will be my next directorial project, hopefully happening, fingers crossed, by the end of the year. It is a -not to give anything away- it is a return to the supernatural, and like “We Are Still Here,” will likely also be a period film.

CS: Is that again for Dark Sky?

Geohegan: I don’t know. Right now, it’s up in the air, I don’t even know if I can answer that. But somebody’s gonna make it.

Mohawk opens theatrically on March 2, with a simultaneous VOD and HD Digital release.

Mohawk

-

Mohawk

-

Mohawk