CS Interview: Aardman’s Nick Park talks directing Early Man

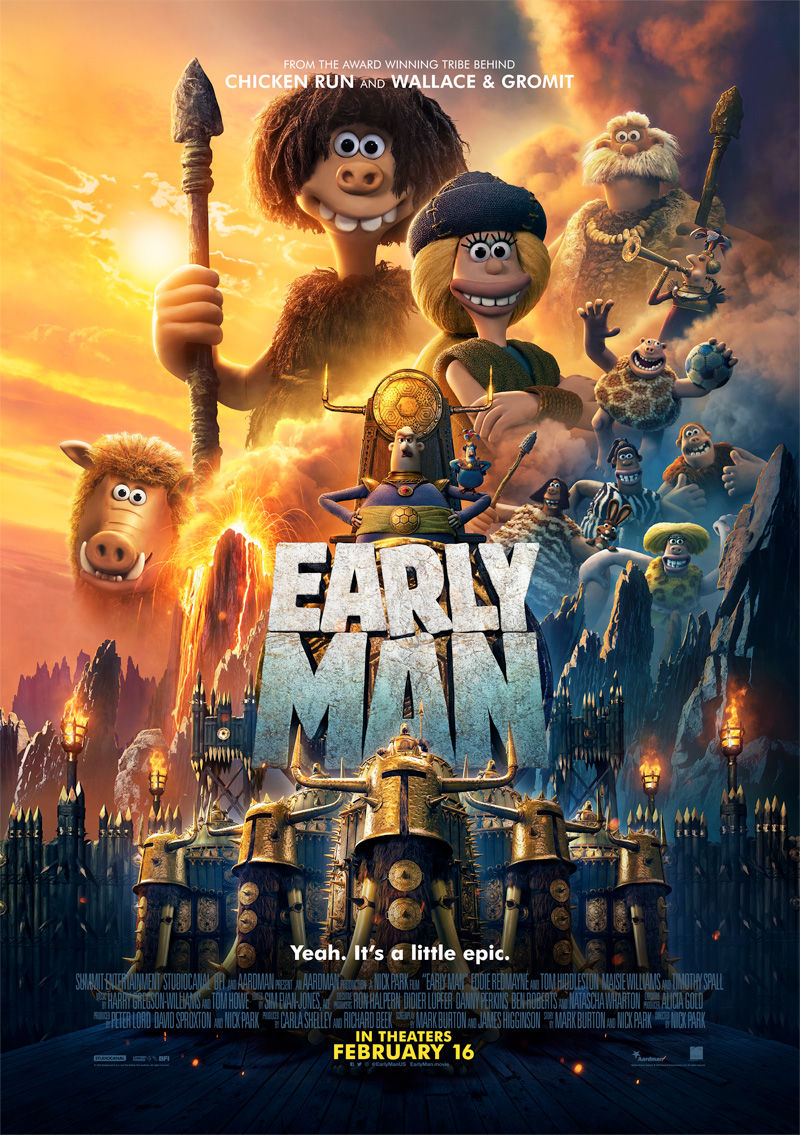

Lionsgate provided ComingSoon.net with the opportunity to talk to Oscar-winning animation director Nick Park, best known as the creator of stop-motion icons Wallace and Gromit as well as Shaun the Sheep. His terrific new stop-motion animated feature Early Man opens in theaters today, his first feature since 2005’s Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, so check out the interview below and check out the movie opening in theaters today!

Set at the dawn of time, when dinosaurs and woolly mammoths roamed the earth, Early Man tells the story of how one brave caveman unites his tribe against a mighty enemy and saves the day!

The Aardman Animations stop-motion animated comedy features the voices of Eddie Redmayne (Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them), Tom Hiddleston (The Avengers), Maisie Williams (Game of Thrones), Timothy Spall (Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street), Richard Ayoade (The IT Crowd), Selina Griffiths (The Smoking Room), Johnny Vegas (Bleak House), Mark Williams (The Harry Potter franchise), Gina Yashere (Kiss Kiss Bang Bang), Simon Greenall (We Need to Talk About Kevin) and Richard Webber.

ComingSoon.net: What made you go away as a director for 12 years, and what brought you back with this project?

Nick Park: In a way, I hadn’t even realized that time had passed. I guess it takes so long to develop projects, and I was involved in overseeing and helping develop other ideas. What brought me to this project? I guess prehistoric people, Stone Age men and women, have always been kind of in my blood. I was a big Ray Harryhausen fan, I still am. “One Million Years B.C.” was my favorite film when I was 11. I couldn’t believe the dinosaurs and people there together, it was beyond my wildest dreams, seeing a big dinosaur kinetic. I guess that was the movie that actually made me pick up a movie camera and start making my own film. I still like cavemen, and they very much suit the medium of stop-frame and the clay animation. The earthiness and the hairiness of the cavemen — there’s something kind of naïve about the technique that suits the primitive nature of the characters.

CS: I remember when I was a kid they had a stop-motion animated caveman show called “Prometheus and Bob,” I don’t know if you’re familiar with that show or not?

Park: No, I don’t think I’m aware of that. I’ve never seen it.

CS: It’s pretty fun! You should check it out. They’re little shorts that aired on Nickelodeon.

Park: I’ll have to look that up.

CS: The movie is obviously totally anachronistic in terms of historical basis. Was that part of the appeal, getting to have fun with history a little bit?

Park: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, with making a caveman comedy, you have to refer to modern culture in different ways, and film culture. It’s definitely important. I was trying to do it in a way that was different to the way “The Flintstones” did it, because that was more about suburban America, but do a kind of British version of “The Flintstones.” Not that we had an aim or anything, but that’s what we kind of ended up doing. Also, I was looking not just to make another caveman adventure, because other people have got that covered, but I was looking for quality angle and a moral argument kind of angle, and that’s where the whole soccer thing came in. How about cavemen inventing soccer, and that’s what appealed to me, was the tribal nature of it, and the way soccer brings people together and helps, in a way, people to become civilized because they’re not fighting anymore. But there’s still, in Britain, in the UK, very much that tribal thing about soccer. It’s almost a religion. So there was a lot of stuff to play with, really, with the Bronze world having got soccer as a religion. In a way, in the modern day, money has very much corrupted the game, and makes it no longer the beautiful game that kids play on a Saturday morning. It’s become this big, money-making thing, and even the fans, how can they afford tickets today?

CS: The DreamWorks Animation movie “The Croods” actually started off at Aardman. Is that kind of where the seeds were planted for your interest in this era?

Park: It is true that it started with us, but I wasn’t really involved with it. It was quite separate, really, but Peter Lord worked on that idea, and then when we split with DreamWorks, they took “The Croods” with them. But I wasn’t really involved, and I had this idea quite separately. It was almost like the cavemen and football kind of came about the same time, really. I mean, the two ideas were kind of prehistoric. It came up as kind of an original take on cavemen. There wasn’t any company to do with “The Croods,” if you know what I mean.

CS: Right, they’re two totally different movies. This one is much more you. The Aardman style has, to me, always been this kind of cheeky-but-gentle humor, and I imagine that clashes sometimes with modern sensibilities, or maybe execs want gross-out humor or faster cutting, stuff like that. How do you resist those sorts of concessions?

Park: I think being based in Bristol, in England, we feel like we’re a bit separate to the whole Hollywood thing, and we sort of just make films. It is very similar to how the guys at Pixar talk: They make films for themselves, and we’re very much like that. We’re very much just — see what makes us laugh. The kind of movies that scared us when we were kids, or made us laugh, the kind of movies we want to see now. We just very much make them for ourselves, and for our own identity, and maintain our own voice.

CS: I’ve always been really curious about the scuttled “Tortoise and the Hare” movie that you guys were working on in the early 2000s. Is there any chance we’ll ever see any of that material released, either as a documentary or something like that?

Park: I don’t know. It’s funny, that was a long time ago now. We don’t really even talk about it much. It’s kind of faded back into the memories of darkest— I mean, maybe, who knows? It was in development at DreamWorks, I guess it’s all gone away now.

CS: Obviously there’s probably no chance of reviving the project, but I think just as a historical aspect of your studio, I think a lot of fans would be interested in seeing what the vision was.

Park: There was some nice footage that was actually made. We did start production. It was nice, and very funny, so I’d be interested to know what’s happened to it. [laughs] I don’t know who’s got it. It’ll turn up sometime, somewhere.

CS: It was a big breakthrough when digital cameras were incorporated into stop-motion. What do you think will be sort of the next breakthrough? Could you imagine a time when the armatures could be controlled more like animatronics and run from a computer, or do you think it will always demand that frame-by-frame hand animation?

Park: I think the two things will remain separate. If it became more definitive, as you’re suggesting, because people called it Go-Motion, didn’t they? Where it was mainly used with creatures or dragons in films like “Dragonslayer,” where they had stop-motion puppets that had a mechanism below the frame. But I guess that, to go back, you’re actually talking about CGI, really. You might as well do it totally independently and without any physical… I don’t know. People are doing motion control, what’s called motion capture, and all these different things. I just love the way stop-frame is, really. I love the clay, and even a lot of stop-frame animators will shy away from using the clay, and also the fur fabrics. But I actually encourage animators to be rough with it, so it’s not at all CG. It looks slightly naïve and a bit rough, and a bit handmade, and not to worry about the fingerprints on the clay. It’s all part of the charm of it. Many years ago, when CGI was really on the rise, with “Toy Story” and what have you, we did used to think our days are numbered, how many films have we got left? But it seems, now, it works for us. There are so many films out, great ones, it helps us stand out, with our own signature.

CS: Yeah, exactly, every time you see one of these movies, it’s very special. Are you guys fostering a new generation of talent there, that can kind of carry on the Aardman legacy?

Park: Yes, definitely. We are training people, and fostering new talent all the time. At the same time, when you think that CG is really the dominant art form out there in animation, there’s still a strong interest in stop-frame with a lot of students and young people. That’s the way it’s always been, in truth, just in handmade products in any way.

CS: I think you’re starting to see a shift away from all-CGI for everything, and you’re starting to see practical make-up effects and practical sets and things like that being reintegrated into filmmaking. I think there will always be a place for stop-motion.

Park: Yeah. There’s something about it, I think. It’s real. It has a sense of something more physical about it. I’m sure CG will do a combo of those things, but we, as an animation and stop-frame studio, we’ve constantly incorporated bits of comparable technology over the years, even in the stop-frame, to help make the job a little easier or a little quicker. Like in this film, most of the principal character animation was all, 90%, stop-frame, but because of the scale of the movie, like on the football pitch, sometimes you couldn’t reach the characters at the back, so we would have to go to digital. And the football crowd itself would be almost entirely digital. We’d just use it where it’s necessary and where it helps, and where it helps to expand the world in this case. It’s very expansive, it’s filmed on very large landscapes. We just didn’t have the studio space, sometimes, so we did composite stuff. We’d put skies in, after, against green screen. Anything you can’t do in clay, you know. Volcano, lava, you know, giant ducks. That’s another example, actually, the giant duck. There’s a certain charm that we tried to maintain. Like the duck, I’m sure you could do beautifully with CGI, but I just wanted to have this sort of Frankenstein, bad taxidermy sort of look. The stop-frame was perfect for that, so we built a massive duck, and animated it.

CS: I know you continue the Wallace legacy with Ben Whitehead, but when the original Wallace voice Peter Sallis passed away last year, how did that make you feel about the work you did with him for so many years, and did it feel kind of like the end of an era?

Park: Yeah. Peter Sallis, I mean, he had such a unique sort of character and quality to the way he did Wallace. It was very hard to shoot the film, really. It was very sad to lose him, but I’m sure he would want us to carry on. My problem is I do have more Wallace and Gromit ideas, I’d love to come back to them. They’re my children, so I love to work with them, come the right time.

CS: There was a time when you said, 20 years ago, that there were going to be no more Wallace and Gromit films, and since then we’ve gotten a movie, we’ve had more shorts, and I’m just glad that you’ve continued the legacy.

Park: I might take a look into continuing, definitely. No solid plans at the moment, though. I’ve got ideas buzzing about in the back of my head!

Early Man is now playing in theaters everywhere.

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man

-

Early Man